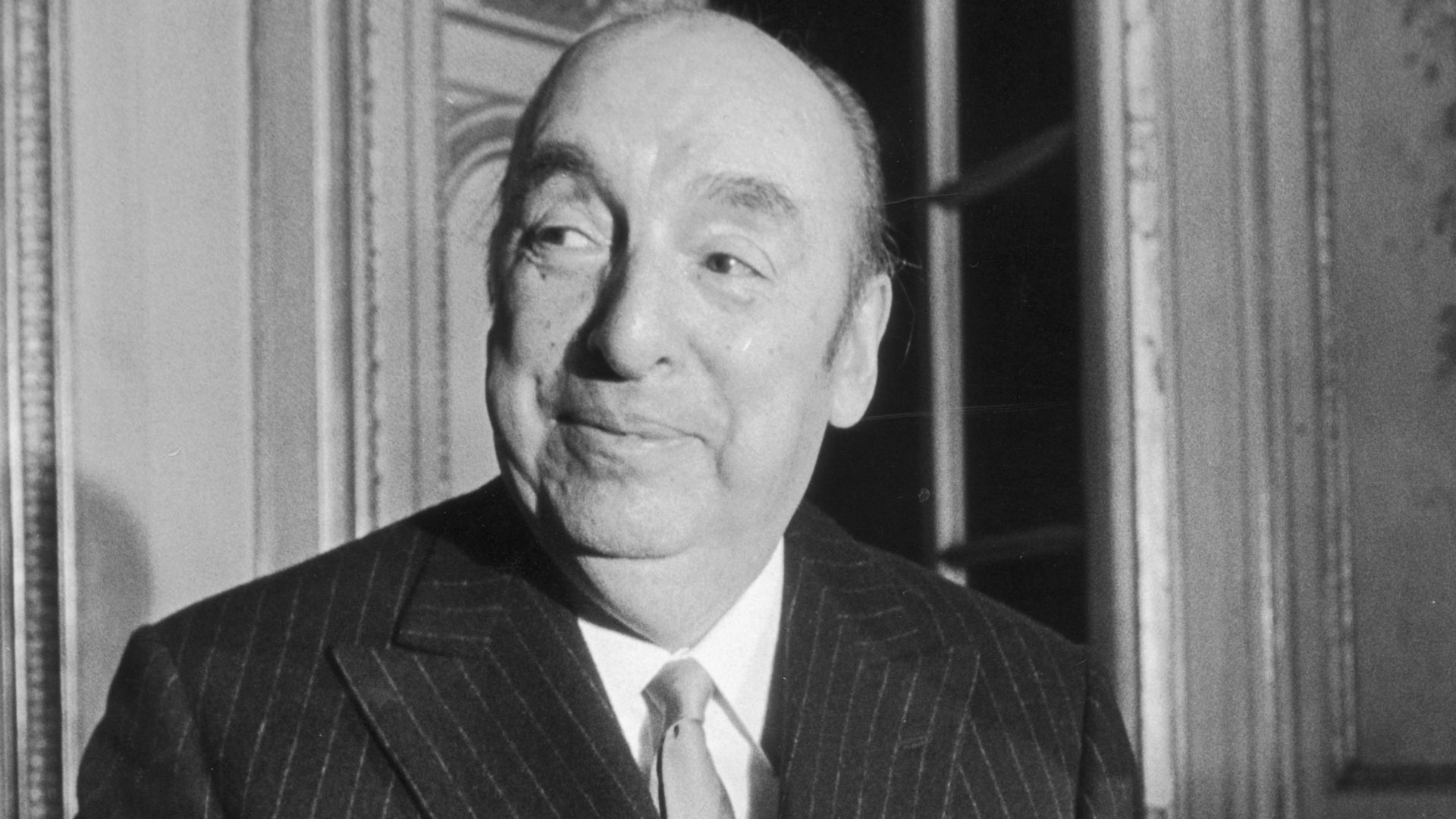

Canto Xii From The Heights Of Macchu Picchu Poem by Pablo Neruda

Canto Xii From The Heights Of Macchu Picchu

Arise to birth with me, my brother.

Give me your hand out of the depths

sown by your sorrows.

You will not return from these stone fastnesses.

You will not emerge from subterranean time.

Your rasping voice will not come back,

nor your pierced eyes rise from their sockets.

Look at me from the depths of the earth,

tiller of fields, weaver, reticent shepherd,

groom of totemic guanacos,

mason high on your treacherous scaffolding,

iceman of Andean tears,

jeweler with crushed fingers,

farmer anxious among his seedlings,

potter wasted among his clays--

bring to the cup of this new life

your ancient buried sorrows.

Show me your blood and your furrow;

say to me: here I was scourged

because a gem was dull or because the earth

failed to give up in time its tithe of corn or stone.

Point out to me the rock on which you stumbled,

the wood they used to crucify your body.

Strike the old flints

to kindle ancient lamps, light up the whips

glued to your wounds throughout the centuries

and light the axes gleaming with your blood.

I come to speak for your dead mouths.

Throughout the earth

let dead lips congregate,

out of the depths spin this long night to me

as if I rode at anchor here with you.

And tell me everything, tell chain by chain,

and link by link, and step by step;

sharpen the knives you kept hidden away,

thrust them into my breast, into my hands,

like a torrent of sunbursts,

an Amazon of buried jaguars,

and leave me cry: hours, days and years,

blind ages, stellar centuries.

And give me silence, give me water, hope.

Give me the struggle, the iron, the volcanoes.

Let bodies cling like magnets to my body.

Come quickly to my veins and to my mouth.

Speak through my speech, and through my blood.

Thankyou so much for putting this up, I don't know if you translated it or not but it just made revising a bit easier! thanks!

Very good translation that transmits very well the original's emotion. Who translated this?

wow! I would love to visit Macchu Picchu someday..an excellent write.. :)

From the age of twenty-one until illness curtailed his ability to travel, Neruda served as diplomatic consul for his native Chile, living in a variety of nations throughout the world. In the years preceding ''The Heights of Macchu Picchu'', he had been acting consul to Spain, during the unfortunate time when fascism was gaining momentum. Neruda relinquished his post and returned to the Americas. Soon after, during the early 1940’s, he traveled to the Andes and saw Macchu Picchu. His journey proved to be a revelatory one, forming the basis of one of his masterpieces. ''The Heights of Macchu Picchu'' is a numbered sequence of twelve poems. Taken as an entity separate from the larger work, it is the product of classic poetic inspiration and indicates a turning point in Neruda’s work. It is a richly imagistic chronicle of the rebirth of the poet’s imagination and heart. The grave disillusion brought about by the tragedy of Spain leads to a renewal of Neruda’s recognition of his need for political action. Neruda’s renewal is told somewhat in the diction of a manifesto: 'Rise up to be born with me, my brother. Give me your hand from the deepzone of your disseminated sorrow... show me the stone on which you felland the wood on which...' [enotes.com]

this poem belongs in ''CANTO GENERAL'' The collection is divided into fifteen sections, each containing from a dozen to more than forty individual poems. It provides a compendium of the poet’s wide range of interests and gathers in one volume the forms he regularly explored during periods throughout his career. Neruda’s passionate interests in history, politics, and nature, and his stunning ability to show the sublime within the mundane are all present in Canto general in full working order. Neruda’s emotional and spiritual history and his evolution as a poetic thinker become entwined with the natural history and political evolution of the southern half of the American continent. ''A Lamp on Earth'', the opening section, begins with ''Amor America (1400) ''. This poem, as do most in this section, operates much in the manner of Neruda’s numerous odes. The book’s first poem conjures the beauty and relative peace of America prior to the arrival of the conquistadores. The succeeding poems of the opening section sing respectively to ''Vegetation'', ''Some Beasts'', ''The Birds Arrive'', ''The Rivers Come Forth'', ''Minerals'' and, finally, ''Man''. ''A Lamp on Earth'' is something of a contemporary 'Popol Vuh', the sequence of ancient Mayan creation myths. Neruda’s work may be more accurately dubbed a re-creation myth. As in the Mayan vision, each separate element of the natural world is treated to its own individual tale of creation. The creation of the world is described as a series of smaller creations —landscape, vegetation, animals, minerals, people— all of which finally exist together as though by way of some godly experiment. The destruction of Mayan culture by the Spanish is detailed in the third section, which concentrates on a selection of names and places. Before moving into that cataclysmic period, however, Neruda inserts one of the most highly regarded works of his career, ''The Heights of Macchu Picchu''.

(ORIGINAL, SPANISH) XII SUBE a nacer conmigo, hermano. Dame la mano desde la profunda zona de tu dolor diseminado. No volverás del fondo de las rocas. No volverás del tiempo subterráneo. No volverá tu voz endurecida. No volverán tus ojos taladrados. Mírame desde el fondo de la tierra, labrador, tejedor, pastor callado: domador de guanacos tutelares: albañil del andamio desafiado: aguador de las lágrimas andinas: joyero de los dedos machacados: agricultor temblando en la semilla: alfarero en tu greda derramado: traed a la copa de esta nueva vida vuestros viejos dolores enterrados. Mostradme vuestra sangre y vuestro surco, decidme: aquí fui castigado, porque la joya no brilló o la tierra no entregó a tiempo la piedra o el grano: señaladme la piedra en que caísteis y la madera en que os crucificaron, encendedme los viejos pedernales, las viejas lámparas, los látigos pegados a través de los siglos en las llagas y las hachas de brillo ensangrentado. Yo vengo a hablar por vuestra boca muerta. A través de la tierra juntad todos los silenciosos labios derramados y desde el fondo habladme toda esta larga noche como si yo estuviera con vosotros anclado, contadme todo, cadena a cadena, eslabón a eslabón, y paso a paso, afilad los cuchillos que guardasteis, ponedlos en mi pecho y en mi mano, como un río de rayos amarillos, como un río de tigres enterrados, y dejadme llorar, horas, días, años, edades ciegas, siglos estelares. Dadme el silencio, el agua, la esperanza. Dadme la lucha, el hierro, los volcanes. Apegadme los cuerpos como imanes. Acudid a mis venas y a mi boca. Hablad por mis palabras y mi sangre.

Passionate testament to the ancient men of Macchu Picchu: the builders, the workers, those who struggled to till the fields and raise the animals, create the beautiful things of that ancient civilization and were the slaves. What a civilization rose and then vanished, only to be discovered in the jungles after centuries, the forbears of today's people. How I honor this poet and those ancient people!

This poem has not been translated into any other language yet.

I would like to translate this poem

This poem is so much more poetic in its original language, Spanish. To truly appreciate this poem, keep this translation on hand and read it in Spanish. Then you will grasp how truly lyrical this poem is.