Two Sages And A Poet Poem by Seshendra Sharma

Two Sages And A Poet

Two sages and a poet

If rivers irrigate a country, poets irrigate the people. Poets are the rivers of metaphors that work on the genetics of the human race.

While Sindhu and Ganga were the centers of Indian culture, Valmiki and Vyasa were the sources of Indian culture. After the center of gravity shifted in Indian life from Sindhu to Ganga, that is, after the Vedic period expired, the new era of epic was opened by the great sage Valmiki. There are no references to the river Sindhu in Ramayana whereas there are innumerable references to Ganga indicting the river's exalted place among the sacred rivers of India.

"dadarsa raaghavo gangaa rishinishevitaam"!

"samudramahisheem gangaam saarasakrounchanaaditaam"!

Vyasa followed the footsteps of Valmiki in perpetuating the Indian culture as represented in Ramayana and adopted the architecture, the building materials of art and the mortar of language, as designed by Valmiki. Kalidasa later followed him in the same line.

A study of Kalidasa's literature in its entirety gives the unmistakable impression that he is the synthesis of the two epics in regard culture, art and language. Simplicity, subtlety and dignity tinctured with a touch of human feeling are the principal elements in the art of these three poets. In fact, it must be said that the two sages and kalidasa are the trinity of Indian culture. It is amazing how the large seas of time that interceded these ‘three poets' and devoured without doubt extensive literature of the times between the three, left these three poets only and upheld them as the chosen ones among scores and scores of poets who intervened them and also perhaps with some distinction.

History of Indian literature shows that Kalidasa was the last outpost of that literary culture which the two sages bequeathed to the nation and after him it showed a steady downward curve of deterioration never again to recover. If we divide Indian Literature into two with Kalidasa as the dividing mark and direct our critical scrutiny at the post-kalidasa period, we find Sanskrit ceasing to be a flowing language in literature and a large measure of artificiality, pedantry and scholastics entering, dominating and almost reducing the mighty river of Sanskrit Literature to the size of a stream and then finally to a trickle, perhaps that was to be the inexorable verdict of time.

Though we cannot overlook the achievements of the authors of ‘Uttara-ram-Charita', 'Kadambari', ‘Karpuramanjari', 'Mrichakatika" and few others in the post Kalidasa period, we cannot overlook the deformities of the period which their works suffer from. Well, we do not see kalidasas any more later on. Perhaps Kalidasa represented the Zenith of the Art of Literature in India and the period has seen finally Indian Literature passing from the world of LOTUS to the world of ROSE.

Enormous work has already been done on Kalidasa by eminent persons, but some vital points escaped notice and they happen to be the most illuminating ones in the study of Kalidasa.

! !

Unless the origins of kalidasa are discovered, the art of Kalidasa and its functions cannot be property appreciated. Such an adventure necessitates a proper perspective and comprehension of the role of Valmiki, the father of Indian Literature. The pre-Valmiki period had no unified Literature capable of exercising a massive influence on people. It was scattered in obsolete Sanskrit and a score or more of Prakrit dialects. Though it was enormous it was tangled fabric. The epic of Valmiki integrates the sprit of all that literature and presents the unified picture of a well defined Indian Culture and Indianity of its literature. Thereby, it turned literature for the first time perhaps, not a mass force and Valmiki was therefore really the first maker of Literature for the people.

Due to the compulsions of the functions it chose, the Epic for the first time turns out thousands of literary expressions unknown before, created for the first time and evoking a pleasant surprise in the listeners. Valmiki was the first and the biggest mint of literary coinage, which alone by and large has been in circulation till now in the literary world in one form or the other. The descriptions of cities, rivers, forests, hills, seasons, human beings, culture, learning, and a whole life received new expression at his hands-

"Grihyscha girisankaashyhi shaaradaambudasannibhyhi! Aalikhantheemivaakaashaam! Dhriyamaanamivaakaasham Uchchrithyrbhavanamutthamyhi! ! Nadeem pushpodupavahaam! Sphatikopameva thoyaaddhaayaam! Jalenotpalagandhinaa! Padmagandhi shivam vaari sukhasheethamanaamayam! Iyam cha nalinee ramyaa! Anekagandhapravaaham punyagandhamanoharam! Dwijasanghanishevitam! Naanaadwijaganayuthaam! Kokilaakulasanaadam! Mattabhramaranaaditam! Mattabarhinahinasanghutshaam!

Meghakrushnaajinadharaa dhaaraa yagyopaveethinaha! Maaruthaapoorithagrihaaha! Praadheetha iva parvathaha! Naanaadhaathusamaakeerna nadee dardurasamyutham! Satya paraakramaha! Satyasangaraha! Krodhamoorchithaha! Krodhasamvarthitekshanaha! Duhkha-moorchchitaha! Buddhimataam varishthaha! Vaakya-vishaaradaha! Vaakyasaarathihi samyag vidyaavrathasnaathaha! Naaganaasoru! subhroo! Bheeroo! Kritagyaha! Satyavaakyaha! Raajaa dasaratho naama dharmasethurivaachalaha! Naahamoupayikee bhaaryaa! Vaasamoupayikeem manye! Sa nirarthangathajale sethum bandhithumichchasi! Tadidam kaakathaaleeyam ghoramaasaaditam mayaa! Satyenyva cha the shape! Yadithe shrothramaagataha! Salile ksheeramaasaktham nishpibanniva saaraha! Aadi!

These are only examples. The lst three may have been picked up from the common parlance of the times. All of them are used by almost all poets in similar contexts up to the time of Harsha's ‘Naishadha'.(who used ‘subhru', 'oupayiki' etc) .

Then, the techniques of story were also followed from Valmiki. Vyasa used Hanuman's flight across the sea, for his Garutman's flight across the sky to reach swarga in Sambhava Parva. The literay language and the imagery were lifted from Ramayana by Vyasa for his purpose. Similarly in Nalopakhyana the description of Damayanti in Chedi is virtually the same as that of Sita in Ashokavana. Vyasa was the first poet to follow Valmiki in this manner and then we find kalidasa a third follower, a most faithful successor in line to the heritage of Valmiki. Some more details will be given as the paper proceeds in suitable contexts.

111

Among the many values that Valmiki projected in his Epic, the most significant one was the essential equality of the King and the sage; in other words, the state and the intellectual. It was this value which Vyasa and kalidasa perpetuated in their works whenever occasion arose. Valmiki describes Dasaratha as ‘Maharshi'.

"MAHARSHIKALPO RAJARSHIHI THRISHU LOKESHU VISHRUTHAHA! "

Rama is described "MAHARSHIKALPENA CHA SANKRITASTADAA, JAGAAMA PUNYAAM GATHIMAATMANAHA SHUBHAAM! '.Vyasa describes Dushyantha as "RAJARSHIHI EVAMUKTVAA SA RAAJARSHIHI TAAMANINDITAGAAMINEEM! "

The king in Ramayana is humble before the sage; and the sage also keeps the king on a higher pedestal than himself. The sages in "Aranyakanda' approach and request Rama to save them from the Raakshasaas(Demons) .

"POOJANEEYASHCHA MAANYASHCHA RAAJA DANDADHAROGURUHU!

Addressing Rama in such terms the sages request

"PARIPAALAYA NO RAMA VADHYAMAANAAN NISHAACHARYHI! "

Now see the reply of Rama: "NYVAMARHATHA MAAM VAKTUM AAGYAAPOHAM TAPASWINAAM"!

This line finds its echo in the first act of Abhijnana Shakuntalam.

Dushyanta says to Brahmans "parigruheetam braahmanavachanam! "

What ever we find in Shakuntalam we find it in Vyasa and earlier in Valmiki. In ‘Arnyakanda", Rama sees the hermitages from a distance. Atonce he relaxes his bow from the string, "ABHYAGACHCHAN MAHATEJaa VIJYAM KRITVAA MAHARDHANUHU"!

It is meant to be a discipline, which the king adopts whenever he is in the vicinity of a hermitage. He pays his visit with all the royal emblems stripped off. Because Rama was a lone figure in the woods followed only by his wife and brother, it was enough to destring his bow in order to observe the discipline. But in Vyasa, Dushyanta was followed by an army and an elaborate retinue. So Vyasa followed what was consequential to Valmiki's principle in the situation to the last limit. Dushyanta asks his army to say at the gate of the hermitage. "DHWAJINEEMASHWASAMBAADHAAM PADAATIGAJASANKULAAM! AVASTHyAAPYA VANADWAARI SONAAMIDAMUVAACHA SAHA! SHTEEYATAAMATRA… YAAVADAAAGAMANAAM MAMA! TATO GACHCHAN MAHABAAHUREKO MAATYAAN VISRIJYATAAN! "

Picking up the thread Kalidaasa says in Shaakuntalam"TAPOVANAVAASINAAM UPARODHO MAA BHOOTH! ETAAVADEVA RATHAM STHAAPAYA YAAVADAVATARAAMI! " In vyaasa Dushyanta says " SAAMAATYO RAAJALINGAANI CHAAPANEEYA NARADHIPAHA! " Kaalidasa turns this into, " VINEETHA VESHA PRAVESHYAANI NAAMA TAPOVANAANI IDAM TAAVAT GRIHYATAAM ITI SOOTHA HASTE DHANUSHCHA AABHARANAANI CHA UPANEEYA"-

Kalidasa highlights this value in many more of his works. In Raghuvasham the visit of King Dileepa to Vashishta's Ashrama is described- "MAA BHOOTH AASHRAMA PEEDITHE PARIMEYAPURASSAROU! "

When the King and the sage meet, Kalidasa says "RAAJYAASHRAMAMUNEEM MUNIHI" In shakuntalam itself "PUNYAASHSHABDHO MUNIRITIMUHUHU KEVALAM RAAJAPOORVAHA"!

Coming back to Shakuntalopakhyana of Vyasa, I shall show it is a miniature Ramayana. When Sita comes meet Rama in Yuddha-kanda after separation, Rama says: " DEEPO NETRAATURASYEVA PRATIKOOLAASI ME DHRIDHAM".

Then Sita turns round and reprimands Rama: "KIM MAAM ASADRISHYAM VAAKYAM EEDRISHAM SHROTHRA DAARUNAM! ROOKSHAM SHRAAVAYASE VEERA, PRAAKRITAHA PRAAKRITAAMIVA! ! APADESHENA JANAKAANNOTPATTIRVASUDHAATALAATH! MAMA VRITTHAM CHA VRITTHAGYA BAHU TENA PURASKRITHAM! "

In the corresponding situation in Vyasa, Shakuntala rebukes Dushyanta "KSHITHOU ATASI RAAJENDRA ANTHARIKSHE CHARAAMYAHAM!

AAVAYORANTARAM PASHYA MERU SARSHAPAYORIVA! "

"RAAJAN, SARSHA MAATRAANI PARACHCHIDRAANI PASHYASI!

AATMANO BILVAMAATRAANI PASHYANNAPI NA PASHYASI! "

Kalidasa avoided this-

Vyasa end Shakuntala like Valmiki end Sita. After Brahma, gods of Heaven and Agni ask Rama to accept Sita. Rama says "ANANYAHRIDAYAAM SITAAM MATH CHCHITTA PARIRAKSHINEEM! AHAMAPYAAVA GACHCHAAMI MYTHILEEM JANAKAATMAJAAM! ! PRATYAYAARTHANTU LOKAANAAM TRAYAANAAM SATYASAMSHRAYAHA! UPEKSHE CHAAPI VYDEHEEM PRAVISHANTHEEM HUTHASHANAM! ! In vyaasa Asaari vani takes the place of Brahma, Agni etc., of Ramayana. Asaarivani asks Dushyanta to accept Shakuntala,

"BHARASVA PUTRAM DUSHYANTHA! MAAVAMAMSTHSAAHA SHAKUNTALAM!

ATHAANTHARIKSHAAT DUSHYANTHAM VAAGUVAACHAA SHAREERINI! "

Like Rama Dushyanta also says receiving Shakuntala, "AHAM CHAAPYEVA ME VYNAM JAANAAMI SVAYAMAATMAJAM BHAVED HI SHANKYO LOKASYA NYVA SHUDDHO BHAVEDAYAM!

Kalidasa's Abhijnana Shakuntalam is assembled of parts taken from the warehouse of Vyasa. Similarly his Meghadootam is an artistic amalgam of the materials drawn from Aranyakanda, Kishkindha kanda and Sundarakanda of Ramayana.

Kalidasa has an eye for the subtle. The fourth Act of Shakuntalam is the very life-breath of the play. The rest are only those that lead to and support it. The world of scholar's considers- "KAAVYESHU NAATAKAM RAMYAM NAATAKESHU SHAKUNTALA! TATRAAPI CHATURTHONKASTATRA SHLOKACHATUSHTAYAM! ! " but behold: Kalidasa's most moving spot in his famous play is however based on 3 slokas of vyasa's Shakkuntalopakhyana, coming in the farewell scene.

A large gathering of the inmates of the Hermitage headed by Kanva bid farewell to Shakuntala. They were all steeped in sorrow of the moment. Shakuntala then makes pradakshina around her father "SHAKUNTALAA CHA PITHARAM ABHIVAADYA KRITHAANJALEEHI! PRADAKSHINEEKRITYA DUHITAA IDAM VAAKYAMABRAVEETH! AJNAANAATH PITHA CHETHI DURAKTHAM CHAAPI VAANRITHAM! AKAARYAM VAANYANISHTSHAM VAA KSHANTUMARHASI KAASHYAPA! EVAMUKTO NATHASHIRAA MUNIRNO VAACHA KINCHANA! MANUSHYA BHAAVAATH KANVOPI MUNIRASHROONYA VARTHAYATH! "

Crammed with feeling, Vyasa moves his listeners to tears with these 3 petit slokas. On the other hand in the 4th Act of Abhijnana Saakuntalam Kanva enters the stage reciting the "sardoola"vritta-

"YAASYATYADYA SHAKUNTALETI HRIDAYAM SANSPRISHTHA MUTKANTHAYAA! KANTHA STHAMBHITA BAASHPAVRITTHI KALUSHAM CHINTAAJADAM DARSHANAM! ! "

Thereby actually rendering Rasa into Vaachya, Kalidasa's Kanva was eloquent of his feelings; Vyasa's Kanva was silent, but shaakuntalam expressive only in action. ("munirnovaacha kinchana")but we can not say that the 4th act of Abhijnana did not receive the admiration of the audience of those times.

The blemishes in Kalidasa as a playwright are more genetic than merely technical. In the synthesis of his system there is a pre-dominant element of Valmiki, which overshadows the feeble element of Vyasa that exists in him. It is important to note here that Valmiki is essentially metaphorical and not so much dramatic. This is an irksome statement, nodoubt which can be negated in some instances of Valmiki. But it can not be denied that there is a larger measure of metaphor than drama in Valmiki, even though the skill displayed by him in handling the dramatic situations is of a rare order. The only instance to my knowledge where metaphor was tremendously exploited to intensify and accentuate the dramatic effect in play is Shakespeare, but that is another matter.

It is necessary here to explain the fundamental differences between the art of ‘vyasa and that of Valmiki. In the farewell scene given above, Vyasa was dramatic pure and simple. Given the same situation Valmiki tends to be metaphorical, even if he wants to be anything else. A similar situation in Ramayana is when Rama comes to take leave of his father and leaves for vanavaasa. The situation was heart-rending. The two given situations in Vyasa and valmiki are exactly identical in that in both the cases the separation of the child and the parent is the poignant point. The differences in sex is merely nominal and makes no difference whatever in the matter of emotional stress of the scene.

Dasaratha the ather in Ramayana cries and cries himself to death in metaphors! Dasaratha beseeches the night to stay away eternally without turning into dawn because Rama leaves for ‘vanavaasa' at dawn.

"na prabhaatham tvayechchaami nishe! nakshatrashaalini!

kriyataam me dayaa bhadre mayaayam rachitonjali! ! "

Sumanta describes the atmosphere of the said moment:

"VISHAYETE MAHARAAJA RAAMAVYASANAKARSHITAAHA!

API VRIKSHAAHA PARIMMLAANAAHA SAPUSHAANKURA KORAKAAHA! !

NISHCHESHTAAHARA-SANCHAARAAHA VRIKSHYKA STHAANA-NISSHITAAHA!

PAKSHINOPI PRAYAACHANTE SARVABHOOTAANUKAMPINAM! !

VYASRIJAN KABALAAN NAAGAAHA GAAVO VASTAAN NA PAAYAYAN! "

This is surely not dramatic description. It is exchanging the whole scene into metaphors. This is the chief characteristic of Valmiki not only here but also all through the Epic. When Ravana enters Janasthana then also see what Valmiki does "sthimitham ganthumaarebhe bhayaath godaavaree nadee! Tamugratejaha karmaanam janasthaanamahaadrumaah! Sameekshya samprakampante! Na pravaati cha maaruthaha!

It is exactly this trend of Art that takes over kalidasa in his renowned 4th act. Just like the trees, animals and birds of Valmiki are emotionally involved, in the human situation. Kalidasa's trees, animals and birds also get involved in the human situation. We have seen valmiki before, and now we will see how Kalidasa in exactly similar situation handling it. Kanva in the 4th Act after entering the stage and expressing his grief on the impending departure of skhakuntala, launches a procession of metaphors with nearly same image as Valmiki:

"BHO BHOHO! SANNIHITAVANADEVATAASTAPOVANATARAVAHA!

PATUM NA PRATHAMAM VYAVASYATI JALAM YUSHMAAVAPEETESHU YAA NAADATTE PRIYAMANDANAAPI BHAVATHAAM SNEHENA YAA PALLAVAM! AADYE VAHA KUSUMAPRASOOTHISAMAYE YASYA BHAVATYUSTAVAHA SEYAM YAATHI SHAKUNTHALAA PATIGRIHAM SARVERANUGYAAYATAAM! ! UDGEERNADARBHAKAVALAA MRIGAAHA PARITYAKTANARTANAA MAYOORAAHA! APASRITAPAANDUPUTRAA MRICHCHATYASHRUNEEVA LATHA! !

I think it can now be seen easily how closely inter-related are the three poets under study. Without a preface like this, the genesis of Kalidasa will remain unexcavated.

Now we reached a stage when we should enter the dialectics of Kavya and try to unravel its profound truths. By a natural tendency Vyasa creates drama whose essence is action. Action is the result of a combination of Vibhaava, anubhaava and vyabhicharibhaava. This leads us finally to the point that Vyasa is basically a Rasa poet. Valmiki on the other hand, in the same emotional sutituation bursts out like a cloud into a shower of metaphors. So, he is an Alankaara poet. Kalidasa obviously contains in his system more of metaphorical faculties like Valmiki and less of the dramatic. For the Indian critics, it is well to know therefore that there is such a basic difference among poets as the Rasa poets and the Alankaara poets. Those that cling instinctively t story or dramatizing it i.e. those that come under the purview of the sargabandha, Akhyaayika, Katha, and Abhineyaartha are Rasa poets. In the modern times they are writers of short stories, novels and plays. Those that indulge in Muktaka poetry i.e. Anibaddha kavita, where vakrokti is the crucial element, are Alankaara poets.

The Rasa poets suffered a decline in Indian literature after the advent of Kalidasa's Meghadootham. Perhaps the ‘sargabandha' and the ‘play', both based on story, were thriving from ages before Kalidasa by sheer force of tradition and must have reached eventually the point of monotony when ‘Meghadootham' appeared on the scene as a reaction against the established trend. Meghadootham marks a total breakaway of the Kavya from the element of story. Kalidasa refused to give a name at least to his Hero ‘Kaschit' thereby meaning to say that it is not the individual but any individual in the given situation will pass through the same emotional experience. It is such emotional experience that is the subject matter of art and not the particular individual, the particular place or time. The Ramagiri Ashrama, the month of Ashaadha the Yaksha and the other constituents of the Kavya lose their significance in Art, if the particular emotional experience did not exist to colour them with an aesthetic meaning so what happened in ‘Meghadootham' was to throw overboard the story and only play on the emotional content of the given human situation. The consequence of setting aside the story in a Kavya was directly dispensing with Rasa. In Meghadootham. Only Bhaava was developed without it's culminating into Rasa. It is therefore a Bhaava Kavya. Critics called it Khanda Kavya or Laghu Kavya and Shri Dwijenranatha Shastri in his ‘Sanskrita-Saahitya-Vimasha'called it Geeti Kaavya.

In fact, Kalidasa's outstanding contribution to Indian literature is his Meghadootam. The reputation of Abhijnaana Shakutalam as a play is only conventional. In fact, it lacks the intensity of drama in it as already explained, though it had the flowers of genius in it.'Raghuvamsham' is not a sargabandha in the strict sense of the term. It was a string of stories, without a unified plot and was a cross between a Rasa-Kavya and Alankaara-Kavya. Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that it marks the advanced stage of the journey of a great poet; whose genius evolved ultimately into simile, the simplest of the figures with the vastest grandeur.

But Meghadootham marks a turning point in Indian Literature, a revolt against the monotony of the repeated production of Rasa-Kavyaas i.e. the plays and the sargabandhas. Time at last needed something fresh and sophisticated, less cumbersome and pithy. Perhaps this phase in Sanskrit literature is like the Romantic period in Europe which started in England with Wordsworth and Coleridge, in France with Hugo, Lamartin, Balzac and others and in Germany Schlegel brothers and Schiller under nearly similar circumstances. Apart from the socio-political conditions behind the Romantic Movement of Europe, at the artistic level of Literature, the prominent and crucial change that literature in this period had undergone was total rejection of story in poetry and the solitary voyage of metaphor on the rough seas of Literature. The ultimate development in this trend was that Edgar Allan Poe declared that there is no long poem and that a poem has to be short necessarily if it has to remain poetic. It is this trend of poetry that the modern world of ours is passing through. It is exactly this trend that kalidasa opened with Meghadootham. Perhaps the story and metaphor keep chasing each other in the cycle of time and perhaps the classical and the romantic periods are revolving phases in the annals of Literature of the Human Race, which seems to be eternally oscillating between sophistication and commonness.

With the advent of Meghadootham, Alankara emerged for the first time like a full moon from the clouds of a Rasa-biased world of those times. Later poets began laying chief emphasis on Alankara even in a Sargabandha wherein the emphasis has to be on Rasa. Poems like ‘Sishupaalavadha' are enjoyed more for their Alankaara than for any skill in handling the plot. Nobody bothered about Rasa in those kavyas any longer. Naturally this led to tremendous repercussions on the contemporary literature and critics.meghadootham had more commentaries than Raghuvamsham; while the former has twenty-four commentaries the later had twenty. It had a spate of imitations, being a totally new genre. From ‘Paarsvaabhudaya' of Jinasena in the 8th century A.D., to "Nemiduta' of Vikram of 17th century, the imitations are numerous. ‘Pavanaduta'of Dhoyi in 12th century, hansasandesham of Vedanta Desika in 14th century, 'Kokila-Sandesha' of Uddanda Kavi again 14th century, 'Hamsaduta' of Vamana Bhatta Baana of 15th century are some examples. It will be revealed on a close study that Harsha Bhatta's ‘Naishadheeya Charitham' is also an echo of Meghadutam. As a result of all this, 'Sandesha-Kavya' became a separate species by itself in Lyrical Literature.

However the most epoch-making event that Meghadootham lead Indian literature to was that Bhamaha closing the era of Rasa in Indian poetics, inaugurated for the first time the era of Alankaara. Naatya-Shaastraas began appearing. Bharata was the first to write Naatya-shaastra and Bhamaha wast the first to write Alankara Shaastra. In his ‘Kavya Alankaara' bhamaha in prefatory chapter itself said: 'NAATAKAM SHAMYAADEENI RAASAK SKANDAKAADI YAATH! TADUKTAMBHINEYAARTHAM UKTONYHI TASYA VISTARAHA! ! '

With this declaration, dispensing with discussion on Rasa, he simply referred his readers to Naatya-shaastraas for the subject and launched the Alankaara on the oceans of Literature, opening the present epoch of Alankaara-shaastra, which has not yet ended. So it must be noted that due to the terrific impact of Meghadootham all the rhetoricians later on in India only followed Bhamaha rejecting discussion of Rasa as a part of Kavya Shastra, Dandi said: ‘MISHRASNI NAATAKAADEENI TESHAAM ANYATRA VISTARAHA! "

Vaamana said: "TALLAKSHANAM NAATEEVA HRIDAYAMITI UPEKSHITAAM ASMAABHIHI! TADANYATAHA GRAAHYAAM!

Then Udbhata declared: "ALANKAARA EVA PRADHAANAMITI PRAACHYAAYAANAAM MATAM! '

It was only Anandavardhana, many centuries later, who introduced some confusion by taking the extreme stand that- "MUKTHESHU PRABANDHESHU RASABANDHAABHINIVESHINAHA KAVAYO DRISHYANTE, YATHAA-HRAMARUKASYA KAVEH MUKTAKAAH SHRINGAARARARASANISHYANDINAHA PRASIDHAA EVA! "

But Abhinavagupta, the renowned commentator of Ananda, clarified the position and dispelled the confusion by stating in his "Lochana" Vyaakhya.

"RASASAMUDAAYO HI NAATYAM-KAAVYE NAATYAAYAMAANA EVA RASAHA! "

With this the confusion ended and Alankaara got firmly entrenched in its position.

V1

Lastly a word about Meghadootam is unavoidable. It will be interesting to make a disclosure here. Meghadootham was produced by Kalidasa by developing a solitary sloka lying hidden behind the leaves and bushes of the Aranya-Kanda of Valmiki-

"ITI VYSHRAVANO RAAJAA RAMBHAASAKTAM PURAANAGHA!

ANUPASTHEEYAMAANO MAAM SANKRUDDHO VYAAJAHAARAHO"

(The episode of viraadha)

It can be easily seen that it was this sloka that blossomed into-

"KASHCHIT KAANTHAA VIRAHA GUROONAA SVAADHEEKAARATH PRAMATTAHA

SHAAPONAASTHANGAMITAMAHIMAA VARSHABHOGYENA BHARTHUHU"-

And developed into the famous Kavya.

Meghadootham was produced by integrating several parts and interweaving several silken threads drawn from Valmiki's Aranya, Kishkindha and Sundara kaandaas. A close scrutiny of Meghadootam clearly reveals to us that there is not a single verse in Meghadootham, which does not have its original in the aforesaid 3 Kandas of Valmiki. The phrase meghadootham itself came to be coined because Hanuman in sundara kanda was repeatedly compared to a ‘Megha".

"BABHOU MEGHA IVAAKAASHE VIDYUDGANAVIBHOOSHITAHA! ! "

Hanuman was called "doota" several times:

"TASYAAHA SAKAASHAM DOOTHOHAM GAMISHYE RAAMASHASANAATH", "AHAM RAAMASYA SANDESHAATH DEVI DOOTASTAVAAGATAHA! "

Hanuman entered Lanka reducing himself to the size of a cat.

"VRISHADAMSHAKA MAATRASSAN VABHOOVAADBHOOTHADARSHANAHA! "

Correspondingly in Meghadootham the Megha was asked t reduce itself to the size of child-elephant to enter ‘Alaka". "GATHVAASADYAHA KALABHATANNUTAAM"

In Ramayana ‘Sita's left eye quivers as an auspicious omen before the event of the arrival of hanumaan in Lanka "PRAASPANDATYKAM NAYANAM SUKESHYAAHA MEENAAHATAM PADMAMIVAABHITAAMRAM! ! "

Similarly when Megha reaches Alakaa, the eye of the Yaksini twitters…."TWAYYASANNE NAYANAMUPARISPANDI SHANKE MRIGAAKSHAYAHA! MEENAKSHOBHAAT CHALAKUVALAYASHREETULAAMESHYATEETI! "

The only difference is in the images chosen for comparison. In the case of ‘Sita' the eye twittered like a lotus shaken by the tail of a fish, whereas in the case of yaksini the eye twittered like a lily shaken by the tail of a fish. It may be noted that in both cases the fish is there to shake the flower delicately with its tail.

The curse of the master on the employee has the same duration in the sloka of aranya-kaanda and the sloka of Meghadootham; and it is also described in terms of Mytho-astronomical symbolism in both cases. In Meghadootham the description is:

"SHAAPAANTHO ME BHUJAGASHAYANAATH UTTHITE SHAARDANGAPAANEE!

This was obviously taken from Kishkindha-kaanda where it lies in its obverse form, "NIDRAA SHAYANYHI KESHAVAMBHYUPYTI! "

Meghadootham taught in our villages in one's adolescent years remains like a hypnotic power, like a fragrant memory haunting him into his old age, recovering to him his bye gone world. It enshrines in its creation the elemental power of the earth, which throws out a tree and a flower as, gifts to man.

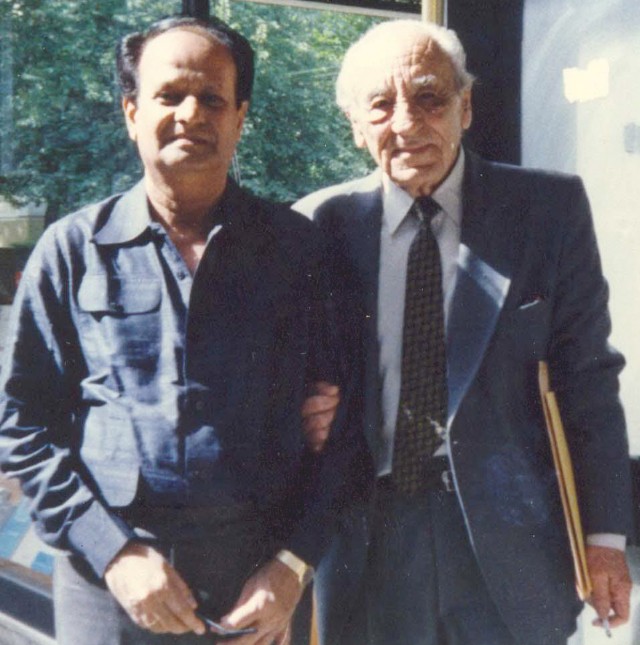

Photo: Seshendra Sharma with Nikhiphoros Vrittakos (Greek Poet)

This poem has not been translated into any other language yet.

I would like to translate this poem