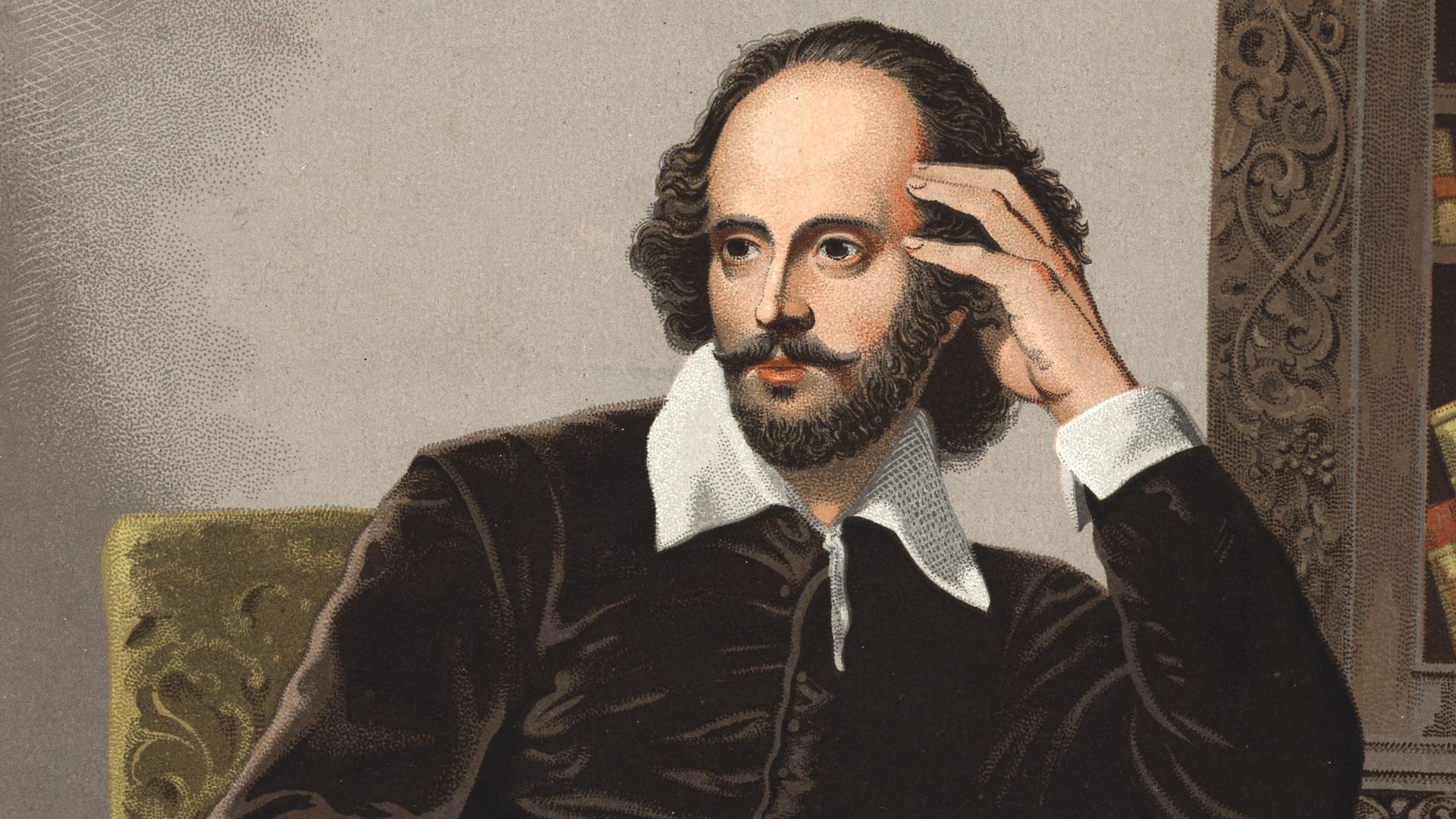

That Time Of Year Thou Mayst In Me Behold (Sonnet 73) Poem by William Shakespeare

That Time Of Year Thou Mayst In Me Behold (Sonnet 73)

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see'st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west;

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death's second self, that seals all up in rest.

In me thou see'st the glowing of such fire,

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the deathbed whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourished by.

This thou perceiv'st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

I have seen it, but not how its looks, That merman are betrayed by sea; When they sails into angler's hooks, And the lions, elephants by the tree; So there you stay, To wail at my grave Turn your back, Speak of my misdeeds Accuse with your flatteries and rave; Tears are shed but death for his greeds With harps, horns or loudy spide; Let no man sing of lamentation or sobbing, Pray but gods weep me to a bed laid aside; And moan another fall of man by sorrowing; That I count it as pity for my hateful misery, Your much griefs, tears is not necessary,

One of many of Shakespeare's many word perfect sonnets. Breathtaking.

This is the perfect example of the 'English' sonnet, which is also called the 'Shakespearian' sonnet: three perfectly parallel quatrains - comparing age to fall of the year, to twilight of the day, and the to dying embers of a fire - and a concluding couplet, transforming a poem on old age to one of Shakespeare's enduring love sonnets. In addition to being an ideal 'English' sonnet, it is also simply a masterpiece of poetry. I'll mention just four prime examples of its poetic excellence: (1) It has a rhyme scheme that, though absolutely regular and tradition, even so reads almost as naturally as conversation; most of the lines are technically end-stopped but they all read with such a pace that the rhymes do not bounce out at you, but subtly underlie the sound of excellence prose (just as Shakespeare's blank verse in his plays, at its best, does) . (2) All three quatrains have beautifully developed metaphors; furthermore, each one has yet another metaphor quite appropriately embedded in it. For example, In the first, quatrain on fall, the trees with only a few leaves left are bare ruined choirs. In the second, on the end of day, night, or, by association, sleep is called Death's second self. The third quatrain on embers has an even more subtle metaphor embedded: the ashes of his youth become the deathbed - a clever reversal of the phoenix myth in which the young fowl springs forth from the ashes of its predecessor, exactly the opposite of 'consumed with that which it was nourished by.'. (3) The simple sounds of Shakespeare's words sing to us - subtly but forcefully. Just to bring this to your consciousness - which is not at all necessary to enjoy it in the poem - notice all the 's' sounds as you read the poem aloud. They keep piling up, echoing each other, climaxing in certain phrases: 'sweet birds sang, ' 'Death's second self, ' Against this slithery, hypnotic sound, the harder but liquid 'l's' keep one floating as if on air, until the lovely climax of the last line: 'To love that well which thou must leave ere long' (love well, leave ere long.) (4) Finally, there is the common, down-to-earth language of most of the poem, most one-syllable words, mostly Anglo-Saxon - all producing their own kind of melodic comfort. All of this is broken unexpectedly and almost rudely with a sudden burst of multisyllabic Latinate phrases: 'which must expire / Consumed with that which it was nourished by. / This thou perceiv'st....' It's almost as if Shakespeare were saying to his reader, 'Now, sit up and listen! What I'm about to say is the most important of all.' Then he concludes and catches us breathless with the conclusion, all single-syllable, all everyday, all Anglo-Saxon: 'which makes thy love more strong / To love that well which thou must leave ere long.' I hope I've made my point about the craftsmanship of Shakespeare's poem. However, now that I've brought it to our awareness, we need to let it slip into our subconscious, not over-emphasizing it. For one of the real merits of the poem is that it reads so easily and gracefully that it's as if we are hearing it within ourselves, letting it float up from the self which could never say it quite so well but wants to. We just let it roll through us, and say, 'Ahh, yes'

I have loved this poem from my first reading many years ago. It is as perfect in itself. It has a lesson on love to all seekers.

Lovely sonnet. Another beautiful piece of poetry from the master poet.

Oh, yes indeed, it is a beautiful piece of poetry written by a master poet. What I would like to hear is what there is about the poem that makes you feel this way about it. Ignore the disrespectful comment below. I am interested in your own reading!

This poem has not been translated into any other language yet.

I would like to translate this poem

I have loved this poem from my first reading 50 years ago. It is as perfect in itself as Bach's Chaconne. It contains several of my favorite things: Autumn, choir - in both meanings, twilight - that between time and thus the tension, and of course, a lesson on love.