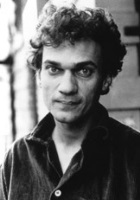

Michael Hofmann

Michael Hofmann Poems

Another one of those Pyrrhic experiences. Call it

an expyrrhience. A day at Lords, mostly rain,

one of those long-drawn-out draws so perplexing to Americans.

...

It's all right

Unless you're either lonely or under attack.

That strange effortful

...

For Hai-Dang Phan

I have no doubt where they will go. They walk

the one life offered from the many chosen.

— Robert Lowell

...

The luncheon voucher years

(the bus pass and digitized medical record

always in the inside pocket come later,

and the constant orientation to the nearest hospital).

...

Annihilating all that's made

To a green thought in a green shade.

— Andrew Marvell

...

Michael Hofmann Biography

Michael Hofmann is a German-born poet who writes in English and a translator of texts from German. Michael Hofmann is the son of the German novelist Gert Hofmann. Hofmann's family first moved to Bristol in 1961, and later to Edinburgh. He was educated at Winchester College and then studied English Literature and Classics. In 1979 he received a BA and in 1984 an MA from the University of Cambridge. In 1983 he started working as a freelance writer, translator, and literary critic. Hofmann has held a visiting professorship at the University of Michigan and currently teaches poetry workshops at the University of Florida. He splits his time between London and Gainesville. In 2008, Hofmann was Poet-in-Residence in the state of Queensland in Australia. He has two sons, Max (1991) and Jakob (1993). Hofmann received the Cholmondeley Award in 1984 for Nights in the Iron Hotel and the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize in 1988 for Acrimony. The same year, he also received the Schlegel-Tieck Prize for his translation of Patrick Süskind's The Double-Bass. In 1993 he received the Schlegel-Tieck Prize again for his translation of Wolfgang Koeppen's Death in Rome. Hofmann was awarded the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 1995 for the translation of his father's novel The Film Explainer, and Michael was nominated again in 2003 for his translation of Peter Stephan Jungk's The Snowflake Constant. In 1997 he received the Arts Council Writer's Award for his collection of poems Approximately Nowhere, and the following year he received the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award for his translation of Herta Müller's novel The Land of Green Plums. In 1999 Hofmann was awarded the PEN/Book-of-the-Month Club Translation Prize for his translation of Joseph Roth's The String of Pearls. In 2000 Hofmann was selected as the recipient of the Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator's Prize for his translation of Joseph Roth's novel Rebellion (Die Rebellion). In 2003 he received another Schlegel-Tieck Prize for his translation of his father's Luck, and in 2004 he was awarded the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize for his translation of Ernst Jünger's Storm of Steel. In 2005 Hofmann received his fourth Schlegel-Tieck Prize for his translation of Gerd Ledig's The Stalin Organ. Hofmann served as a judge for the Griffin Poetry Prize in 2002, and in 2006 Hofmann made the Griffin's international shortlist for his translation of Durs Grünbein's Ashes for Breakfast.)

The Best Poem Of Michael Hofmann

Cricket

Another one of those Pyrrhic experiences. Call it

an expyrrhience. A day at Lords, mostly rain,

one of those long-drawn-out draws so perplexing to Americans.

Nothing riding on the game, two mid-table counties

at the end of a disappointing season, no local rivalry or anything like that,

very few people there, the game itself going nowhere slowly

on its last morning. The deadest of dead rubbers.

Papa had his beer, but you two must have wondered what you'd done wrong.

Did I say it was raining, and the forecast was for more rain?

Riveting. A way, at best, for the English

to read their newspapers out of doors, and get vaguely shirty

or hot under the collar about something. The paper, maybe, or the rain.

Occasionally lifting their eyes to watch the groundsmen at their antics,

not just hope over experience but hope over certain knowledge.

It was like staying to watch your horse lose.

And yet there was some residual sense of good fortune to be there,

perhaps it was the fresh air or being safely out of range of conversation

or the infinitesimal prospect of infinitesimal entertainment.

One groundsman—the picador—mounted on a tractor,

others on foot, like an army of clowns, with buckets and besoms.

The tractor was towing a rope across the outfield to dry it—

we saw the water spray up, almost in slow motion—

as from newly cut hair. The old rope was so endearingly vieux jeu.

It approached a pile of sawdust—two failing styles of drying—

and one of the groundsmen put out his foot to casually flick it over,

as sporting a gesture as we expected to see all day

in terms of finesse, economy of movement, timing.

He missed, and instead the rope sliced right through the sawdust pile,

and flattened it. A malicious laugh, widely dispersed and yet unexpectedly hearty,

went up on all sides of the ground. Soft knocks that school a lifetime—no?