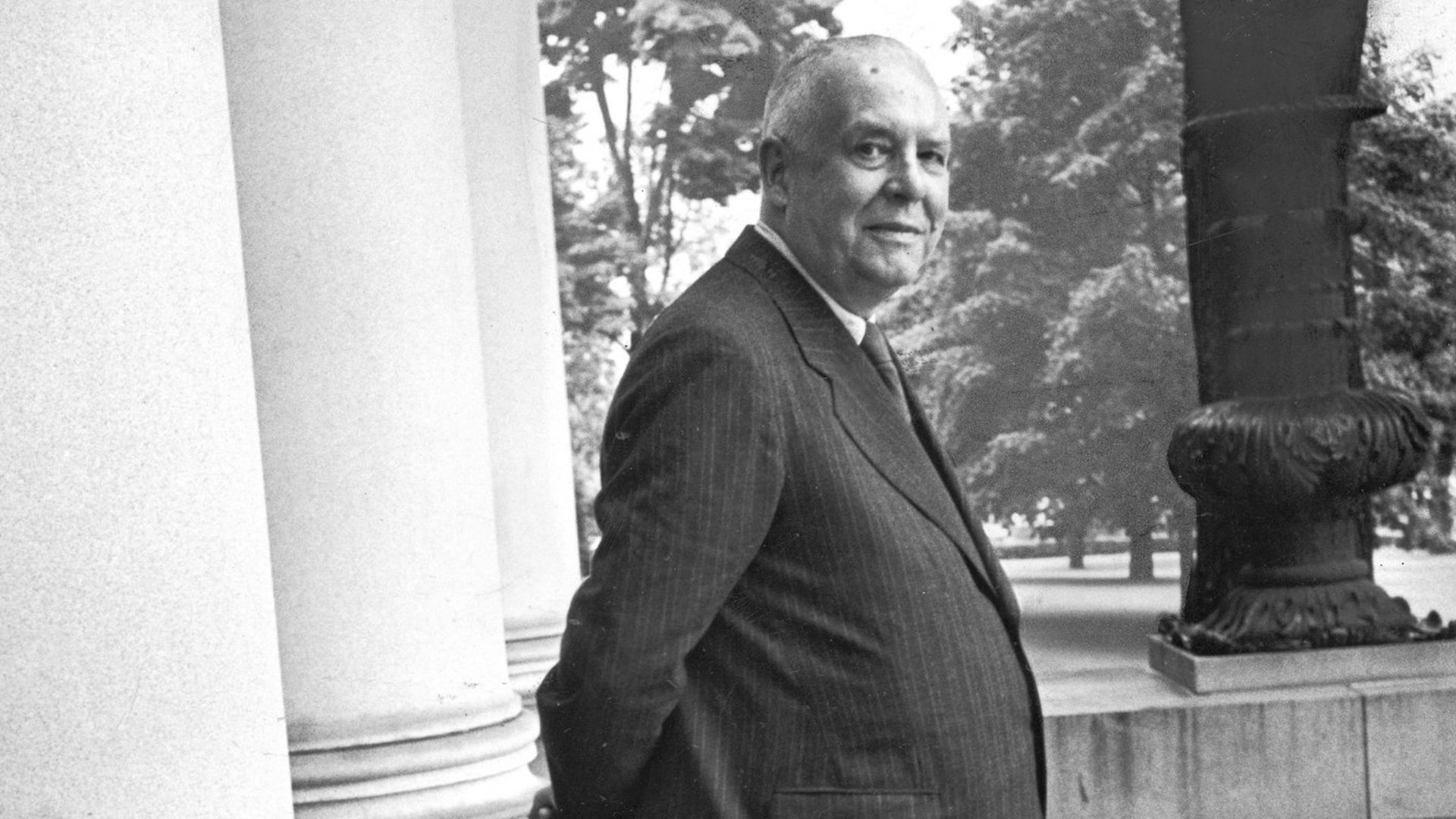

Looking Across The Fields And Watching The Birds Fly Poem by Wallace Stevens

Looking Across The Fields And Watching The Birds Fly

Among the more irritating minor ideas

Of Mr. Homburg during his visits home

To Concord, at the edge of things, was this:

To think away the grass, the trees, the clouds,

Not to transform them into other things,

Is only what the sun does every day,

Until we say to ourselves that there may be

A pensive nature, a mechanical

And slightly detestable operandum, free

From man's ghost, larger and yet a little like,

Without his literature and without his gods . . .

No doubt we live beyond ourselves in air,

In an element that does not do for us,

so well, that which we do for ourselves, too big,

A thing not planned for imagery or belief,

Not one of the masculine myths we used to make,

A transparency through which the swallow weaves,

Without any form or any sense of form,

What we know in what we see, what we feel in what

We hear, what we are, beyond mystic disputation,

In the tumult of integrations out of the sky,

And what we think, a breathing like the wind,

A moving part of a motion, a discovery

Part of a discovery, a change part of a change,

A sharing of color and being part of it.

The afternoon is visibly a source,

Too wide, too irised, to be more than calm,

Too much like thinking to be less than thought,

Obscurest parent, obscurest patriarch,

A daily majesty of meditation,

That comes and goes in silences of its own.

We think, then as the sun shines or does not.

We think as wind skitters on a pond in a field

Or we put mantles on our words because

The same wind, rising and rising, makes a sound

Like the last muting of winter as it ends.

A new scholar replacing an older one reflects

A moment on this fantasia. He seeks

For a human that can be accounted for.

The spirit comes from the body of the world,

Or so Mr. Homburg thought: the body of a world

Whose blunt laws make an affectation of mind,

The mannerism of nature caught in a glass

And there become a spirit's mannerism,

A glass aswarm with things going as far as they can.

This is a challenging poem. It is, or appears to be, a strictly philosophical poem. More precisely, it appears to be a strictly epistemological poem. Still, I wonder who Mr. Homburg is (I presume he is not Anthony Eden): I would like to define his “irritating minor idea” a little more expressly; I want to delve a little more deeply into Mr. Stevens’ objections to that idea; and I would like to be able to say what Mr. Stevens prefers in its place. Some commenters have identified Mr. Homburg with Emerson and the transcendentalists including Thoreau, Fuller, Parker and others. I have no objection to that linkage, but I would like to point out that much of Stevens’ poetry is firmly rooted in the transcendentalist tradition. See “Poem Written at Morning” for just one example. In this context I understand transcendentalism to be a viewpoint in which knowledge or truth is discovered not just rationally but intuitively as well. In a sense, our “God-given” intuitive faculty or imagination is as much a source of truth and knowledge as our reasoning mind. In other words, our intuition allows us to “transcend” the limits of our reason alone. Leaving aside Stevens’ agnosticism (just for a moment that is) , compare the role of intuition in the transcendentalist view with Stevens’ lines in “Of Modern Poetry, ” where he says that when we compose our “poem of the mind” (i.e., when we search for truth) we must “[w]ith meditation, speak words that in the ear, /In the delicatest ear of the mind, repeat, /Exactly, that which it wants to hear, at the sound /Of which, an invisible audience listens, /Not to the play, but to itself.” It seems to me that the parallels cannot be denied. The interaction between intuition (“the delicatest ear of the mind”) and rationality (the “invisible audience”) is clear and express. Perhaps, when he refers to Mr. Homburg’s “irritating minor ideas, ” Stevens is admitting that he is just quibbling, and that he agrees in principle with most of Mr. Homburg’s other ideas. However, I don’t quite see it that way. The reference seems to be entirely dismissive, and appears to belittle all of Mr. Homburg’s ideas, irritating or not. (Still I myself have to admit that as an attorney and vice president for the Hartford, Stevens surely built a career on quibbling.) As for a definition of this particular “irritating minor idea, ” let me try to break it down as follows: a) day by day, the sun merely “thinks away” the grass, trees and clouds, without transforming them into anything different; b) until we allow for the existence of a “pensive” Nature (which Stevens editorializes as being mechanical and detestable—never mind the contradiction between pensive and mechanical) , having an undefined mental process (“too much like thinking to be less than thought”) independent of man (“and yet a little like” man) , we will find ourselves living in chaos (an element “too big, ” “not planned, ” and “without any form or any sense of form”): and c) if we live in chaos, then (because “What we know [is] in what we see, what we feel [is] in what /We hear, [and] what we are, beyond mystic disputation, [is] /In the tumult of integrations out of the sky”) our own thought processes become meaningless—our thoughts become a mere tautology (they are “a breathing like the wind, /A moving part of a motion, a discovery /Part of a discovery, a change part of a change”) . As a “new scholar replacing an older one, ” Stevens “reflects /A moment on this fantasia. He seeks /For a human that can be accounted for.” If, as Mr. Homburg apparently believes, “The spirit comes from the body of the world, ” and that world is chaotic (with only “blunt laws, ” obtuse and imprecise) then our minds become mere affectations, our thoughts mere “mannerisms, ” and we ourselves are likened to “A glass aswarm with things going as far as they can.” And how far can anything go if it is contained in a glass? (On the other hand, see “Anecdote of the Jar.”) Now, just like any good lawyer, Stevens here has not stated his opponent’s argument in the best light. If I understand Mr. Homburg’s irritating little idea, it is this: a) one must trust one’s intuition (so far so good, says Stevens): b) Mr. Homburg’s intuition tells him there is a natural intelligence operating in the universe (well, okay…): c) his intuition further tells him that without that natural intelligence we would all be living in chaos (uh, yeah, maybe): therefore, d) we must all believe in the existence of a natural intelligence, or God (no, no, no—stop right there) . It seems to me that Stevens’ fundamental objection to Mr. Homburg’s irritating little idea is in the proposition that one must intuitively conclude that God exists, in order to impose order upon the world and impart meaning to our lives. Stevens has long ago accepted the notion that we live in a beautiful and chaotic world. (See “Sunday Morning, ” where Stevens says, “We live in an old chaos of the sun.”) He does not agree with Mr. Homburg’s premise that “To think away the grass, the trees, the clouds, /Not to transform them into other things, /Is only what the sun does every day.” He does not see a pensive nature. He sees, and accepts, a chaotic one, or perhaps a nature founded more upon Chemistry than on Thought. Moreover, he would insist, I believe, that one imparts one’s own meaning to one’s life, God or no God. In short, Stevens does not believe that a chaotic Nature is a threat to man’s search for meaning. It provides a challenge, to be sure. But we can order our own lives by seeking and obtaining that which will “suffice.” (Of Modern Poetry.) We may do so by means of fiction—poetry, after all, being the “supreme fiction”—provided that fiction “suffices.” Having said that, however, I also concede that Stevens’ mood with respect to this issue was somewhat mercurial. His agnosticism as he was writing “Looking Across Fields” seems to be stronger than when he was writing “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour, ” with its references to a “central mind, ” and the “intensest rendezvous.” In the larger context of his work, it seems to me Stevens has concluded that any answer to the question of “Does God exist? ” is a personal one, and cannot be imposed upon others, whether by way of a “pensive nature” or otherwise. Lastly in this regard, there is the sentence “The spirit comes from the body of the world, /Or so Mr. Homburg thought.” I think that Stevens would probably disagree with this sentiment as well, and reply that if there is a God (a proposition that Stevens might or might not accept) , then the spirit does not come from the body of the world. It comes from God. Moreover, if there is no God (again a proposition that Stevens might or might not accept) then it is premature to suppose that the spirit (such as it is) comes from the body of the world. Stevens would likely object to the notion that one can answer the question “Does God exist? ” by looking exclusively to the “intelligence” of nature. Ironically, Mr. Homburg’s answer to the question (as stated by Stevens) seems in the end to exclude intuition, and rely instead on external or deductive reasoning—a reasoning which Stevens sees as faulty.

Question for Gary Witt. Have you published a paper, or a book, in which you present this reading, or one similar to it? If so, would you provide a link to it? Thank you.

Stop thinking. Poetry isn't philosophy. Experience the words directly. Read them aloud, feel them, and move on. Don't process them.

This poem has not been translated into any other language yet.

I would like to translate this poem

We think as wind skitters on a pond in a field - - Yes, that is what I am doing now and my thoughts are like leaves that left in the wing