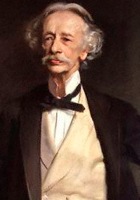

Coventry Patmore

Coventry Patmore Poems

I walk, I trust, with open eyes;

I've travelled half my worldly course;

And in the way behind me lies

Much vanity and some remorse;

...

It was not like your great and gracious ways!

Do you, that have naught other to lament,

Never, my Love, repent

Of how, that July afternoon,

...

My little Son, who look'd from thoughtful eyes

And moved and spoke in quiet grown-up wise,

Having my law the seventh time disobey'd,

I struck him, and dismiss'd

...

Here, in this little Bay,

Full of tumultuous life and great repose,

Where, twice a day,

The purposeless, gay ocean comes and goes,

...

All night fell hammers, shock on shock;

With echoes Newgate's granite clang'd:

The scaffold built, at eight o'clock

...

With all my will, but much against my heart,

We two now part.

My Very Dear,

Our solace is, the sad road lies so clear.

...

Why, having won her, do I woo?

Because her spirit's vestal grace

Provokes me always to pursue,

But, spirit-like, eludes embrace;

...

Love, light for me

Thy ruddiest blazing torch,

That I, albeit a beggar by the Porch

Of the glad Palace of Virginity,

...

'IF I were dead, you'd sometimes say, Poor Child!'

The dear lips quiver'd as they spake,

And the tears brake

From eyes which, not to grieve me, brightly smiled.

...

A woman is a foreign land,

Of which, though there he settle young,

A man will ne'er quite understand

The customs, politics, and tongue.

...

Not in the crisis of events

Of compass'd hopes, or fears fulfill'd,

Or acts of gravest consequence,

Are life's delight and depth reveal'd.

...

Heroic Good, target for which the young

Dream in their dreams that every bow is strung,

And, missing, sigh

Unfruitful, or as disbelievers die,

...

An idle poet, here and there,

Looks around him; but, for all the rest,

The world, unfathomably fair,

Is duller than a witling's jest.

...

Whene'er mine eyes do my Amelia greet

It is with such emotion

As when, in childhood, turning a dim street,

I first beheld the ocean.

...

The crocus, while the days are dark,

Unfolds its saffron sheen;

At April's touch the crudest bark

...

Beneath the stars and summer moon

A pair of wedded lovers walk,

Upon the stars and summer moon

They turn their happy eyes, and talk.

...

Suspicion's playful counterfeit

Begot your question strange:

The only thing that I forget

Is that there's any change.

...

In Gerald's Cottage by the hill,

Old Gerald and his child,

Innocent Maud, dwelt happily;

...

I The Paragon

When I behold the skies aloft

Passing the pageantry of dreams,

...

Coventry Patmore Biography

Coventry Kersey Dighton Patmore was an English poet and critic best known for The Angel in the House, his narrative poem about an ideal happy marriage. Life Youth The eldest son of author Peter George Patmore, Coventry Patmore was born at Woodford in Essex and was privately educated. He was his father's intimate and constant companion and inherited from him his early literary enthusiasm. It was Coventry's ambition to become an artist. He showed much promise, earning the silver palette of the Society of Arts in 1838. In 1839 he was sent to school in France for six months, where he began to write poetry. On his return, his father planned to publish some of these youthful poems; Coventry, however, had become interested in science and poetry was set aside. He later returned to writing however, enthused by the success of Alfred Lord Tennyson; and in 1844 he published a small volume of Poems, which was original but uneven. Patmore, distressed at its reception, bought up the remainder of the edition and destroyed it. What upset him most was a cruel review in Blackwood's Magazine; but the enthusiasm of his friends, together with their more constructive criticism, helped foster his talent. The publication of this volume bore immediate fruit in introducing its author to various men of letters, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, through whom Patmore became known to William Holman Hunt, and was thus drawn into the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, contributing his poem "The Seasons" to The Germ. Major work At this time Patmore's father was financially embarrassed; and in 1846 Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton obtained for Coventry the post of printed book supernumary assistant at the British Museum, a post he occupied for nineteen years, devoting his spare time to poetry. In 1847 he married Emily Andrews, daughter of Dr. Andrews of Camberwell and by 1851 they had had two sons, Coventry (born 1848) and Tennyson (born 1850). Three daughters followed - Emily (born 1853), Bertha (born 1855) and Gertrude (born 1857), before their last child, a son (Henry John), was born in 1860. At the British Museum Patmore was instrumental in starting the Volunteer Movement in 1852. He wrote an important letter to The Times on the subject, and stirred up much martial enthusiasm among his colleagues. In 1853 he republished Tamerton Church Tower, the more successful of his pieces from Poems of 1844, adding several new poems which showed distinct advance, both in conception and treatment; and in the following year (1854) the first part of his best known poem, The Angel in the House appeared. The Angel in the House is a long narrative and lyric poem, with four sections composed over a period of years: The Betrothed and The Espousals (1854) which eulogize his first wife; followed by Faithful For Ever (1860); and The Victories of Love (1862). The four works were published together in 1863 and have come to symbolise the Victorian feminine ideal - which was not necessarily the ideal amongst feminists of the period. By 1861 the family were living in Elm Cottage, North End, Hampstead. In 1862 Emily died after a lengthy and lingering illness, and shortly afterwards Coventry joined the Roman Catholic church. In 1865 he re-married, his second wife being Marianne Byles, daughter of James Byles of Bowden Hall, Gloucester; a year later he purchased Buxted Hall in Surrey, the history of which he wrote in How I managed my Estate (1886). In 1877 he published The Unknown Eros, which contains his finest poetic work, and in the following year Amelia, his own favourite among his poems, together with an interesting essay on English Metrical Law, appeared. This departure into criticism continued in 1879 with a volume of papers entitled Principle in Art, and again in 1893 with Religio poetae. His second wife Marianne died in 1880, and in 1881 he married Harriet Robson from Bletchingley in Surrey (born 1840). Their son Francis was born in 1882. In later years he lived at Lymington, where he died in 1896. He was buried in Lymington churchyard. Evaluation A collected edition of Patmore's poems appeared in two volumes in 1886, with a characteristic preface which might serve as the author's epitaph. "I have written little," it runs; "but it is all my best; I have never spoken when I had nothing to say, nor spared time or labour to make my words true. I have respected posterity; and should there be a posterity which cares for letters, I dare to hope that it will respect me." The sincerity which underlies this statement, combined with a certain lack of humour which peers through its naïveté, points to two of the principal characteristics of Patmore's earlier poetry; characteristics which came to be almost unconsciously merged and harmonized as his style and his intention drew together into unity. His best work is found in the volume of odes called The Unknown Eros, which is full not only of passages but entire poems in which exalted thought is expressed in poetry of the richest and most dignified melody. Spirituality informs his inspiration; the poetry is glowing and alive. The magnificent piece in praise of winter, the solemn and beautiful cadences of "Departure," and the homely but elevated pathos of "The Toys," are in their manner unsurpassed in English poetry. His somewhat reactionary political opinions, which also find expression in his odes, are perhaps a little less inspired, although they can certainly be said to reflect, as do his essays, a serious and very active mind. Patmore is today one of the least known but best-regarded Victorian poets. His son Henry John Patmore (1860–1883) also became a poet. Trivia Coventry Patmore was caricatured as the unpleasant poet Carleon Anthony in Joseph Conrad's novel Chance (1913). In X-Men: Season 1 Episode 1 Patmore's poem "Farewell", from the collection "The Unknown Eros", is paraphrased by the character Beast, "The faint heart averted many feet and many a tear, in our opposed path to perservere." The character also follows the quote with, "A minor poet for a minor obstacle.")

The Best Poem Of Coventry Patmore

Love's Reality

I walk, I trust, with open eyes;

I've travelled half my worldly course;

And in the way behind me lies

Much vanity and some remorse;

I've lived to feel how pride may part

Spirits, tho' matched like hand and glove;

I've blushed for love's abode, the heart;

But have not disbelieved in love;

Nor unto love, sole mortal thing

Or worth immortal, done the wrong

To count it, with the rest that sing,

Unworthy of a serious song;

And love is my reward: for now,

When most of dead'ning time complain,

The myrtle blooms upon my brow,

Its odour quickens all my brain.

The poem Toys is very symbolic in its setting. Even though the poet speaks of his little son, from a broader perspective, the poem underlies the 'comfort' man resorts to, when God admonishes him... When man is buffeted for his faults, or when he encounters certain undesirable happenings in his life, he immediately resorts to other resorts to comfort and solace him, thus moving away from his creator. But still, God, much akin to Francis Thompson's 'Hound of Heaven, ' in all His grace forgives man for his shortcomings and kisses him (blesses him with His heavenly comfort) . The creator’s concern for His creation and the creation’s antipathy to the love of God are manifested in this poem. The slumber of the child represents the forgetfulness and the sheer childish callousness of children towards elders (here God) . The lines “anged there with careful art, To comfort his sad heart” are of particular significance because, man in his love of the world, forgets whatever blessings he has derived from the Almighty and turns to the world in times of distress. The poem has a great import on the love of God and the antipathy of man.