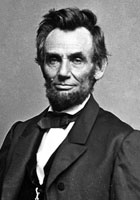

Abraham Lincoln Biography

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and promoting economic and financial modernization. Reared in a poor family on the western frontier, Lincoln was mostly self-educated. He became a country lawyer, an Illinois state legislator, and a one-term member of the United States House of Representatives, but failed in two attempts to be elected to the United States Senate.

After opposing the expansion of slavery in the United States in his campaign debates and speeches, Lincoln secured the Republican nomination and was elected president in 1860. Before Lincoln took office in March, seven southern slave states declared their secession and formed the Confederacy. When war began with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Lincoln concentrated on both the military and political dimensions of the war effort, seeking to reunify the nation. He vigorously exercised unprecedented war powers, including the arrest and detention without trial of thousands of suspected secessionists. He prevented British recognition of the Confederacy by skillfully handling the Trent affair late in 1861. He issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and promoted the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, abolishing slavery.

Lincoln closely supervised the war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including commanding general Ulysses S. Grant. He brought leaders of various factions of his party into his cabinet and pressured them to cooperate. Under his leadership, the Union set up a naval blockade that shut down the South's normal trade, took control of the border slave states at the start of the war, gained control communications with gunboats on the southern river systems, and tried repeatedly to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond. Each time a general failed, Lincoln substituted another until finally Grant succeeded in 1865. An exceptionally astute politician deeply involved with power issues in each state, he reached out to War Democrats and managed his own re-election in the 1864 presidential election.

As the leader of the moderate faction of the Republican party, Lincoln found his policies and personality were "blasted from all sides": Radical Republicans demanded harsher treatment of the South, War Democrats desired more compromise, Copperheads despised him, and irreconcilable secessionists plotted his death. Politically, Lincoln fought back with patronage, by pitting his opponents against each other, and by appealing to the American people with his powers of oratory.His Gettysburg Address of 1863 became the most quoted speech in American history. It was an iconic statement of America's dedication to the principles of nationalism, equal rights, liberty, and democracy. At the close of the war, Lincoln held a moderate view of Reconstruction, seeking to speedily reunite the nation through a policy of generous reconciliation in the face of lingering and bitter divisiveness. But six days after the surrender of Confederate commanding general Robert E. Lee, Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth at Ford's Theatre. His death was the first assassination of a U.S. president and sent the northern parts of the country into mourning. Lincoln has been consistently ranked by scholars and the public as one of the three greatest U.S. presidents

Poetry

Throughout his life, Abraham Lincoln was an avid reader of poetry. As a teenager, however, Lincoln also began to cultivate an interest in writing poetry. Lincoln's oldest surviving verses, written when he was between fifteen and seventeen years old, are brief squibs that appear in his arithmetic book.

During his teens and early twenties, Lincoln wrote a number of crude and satirical verses. The poem that Lincoln's neighbors best remembered from this period was the "Chronicles of Reuben," which his neighbor, Joseph C. Richardson, claimed was "remembered here in Indiana in scraps better than the Bible." The history behind the poem reveals that, when provoked, Lincoln could wield his pen as a blunt instrument of attack. In 1826, Lincoln's sister Sarah married Aaron Grigsby, whose family were neighbors of the Lincolns. When Sarah died in childbirth in 1828, Lincoln blamed Aaron and the Grigsbys for delaying to call a doctor. The incident created a rift between Lincoln and the Grigsbys. Lincoln's bitterness increased when he was not invited to the joint wedding celebration of Aaron's brothers Reuben and Charles, who married on the same day. In revenge, Lincoln appears to have arranged, through a friend, for Reuben and Charles to be brought to the wrong bedrooms, where each other's new wives awaited after the wedding party. Lincoln then wrote a description of the incident known as the "Chronicles of Reuben" as payback. Patterned after biblical scripture, the prose narrative was followed by a poem about Billy Grigsby, another of Aaron's brothers. The coarse poem ridicules the failed attempts of Billy to woo girls. The original text of the "The Chronicles of Reuben" does not survive, though several of Lincoln's neighbor's later recollected the poem for William Herndon.

One of Lincoln's Springfield neighbors, James Matheny, recalled that sometime between 1837-39 Lincoln joined "a Kind of Poetical Society" to which he occasionally submitted poems. Although none of the poems survive, Matheny remembered one eye-raising stanza from a poem "on Seduction":

Whatever Spiteful fools may Say —

Each jealous, ranting yelper —

No woman ever played the whore

Unless She had a man to help her.

Lincoln wrote his most serious poetry in 1846. The limited information that exists about their composition comes from comes from Lincoln's correspondence with Andrew Johnston, a fellow lawyer and Whig politician from Quincy, Illinois. In a letter to Johnston on February 24, 1846, Lincoln wrote:

Feeling a little poetic this evening, I have concluded to redeem my promise this evening by sending you the piece you expressed the wish to have. You find it enclosed. I wish I could think of something else to say; but I believe I can not. By the way, would you like to see a piece of poetry of my own making? I have a piece that is almost done, but I find a deal of trouble to finish it.

The poem Lincoln alluded to is "My Childhood-Home I See Again." It was completed shortly after Lincoln's message to Johnston

When Lincoln later edited the poem, he divided it into two sections, or cantos. He sent the first canto to Johnston in an April 18, 1846 letter, noting that it was intended to be the first section of a larger poem he was working on. In the letter, Lincoln preceded the text of the canto by describing the circumstances that led him to write it:

In the fall of 1844, thinking I might aid some to carry the State of Indiana for Mr. Clay, I went into the neighborhood in that State in which I was raised, where my mother and sister were buried, and from which I had been absent about fifteen years. That part of the country is, within itself, as unpoetical as any spot of the earth; but still, seeing it and its objects and inhabitants aroused feelings in me which were certainly poetry; though whether my expression of those feelings is poetry is quite another question. When I got to writing, the change of subjects divided the think into four little divisions or cantos, the first only of which I send you now and may send the others hereafter.

Lincoln sent the second canto to Johnston in his letter of September 6, 1846. Lincoln introduced the canto to Johnston in the following manner:

You remember when I wrote you from Tremont last spring, sending you a little canto of what I called poetry, I promised to bore you with another some time. I now fulfil the promise. The subject of the present one is an insane man. His name is Matthew Gentry. He is three years older than I, and when we were boys we went to school together. He was rather a bright lad, and the son of the rich man of our very poor neighbourhood. At the age of nineteen he unaccountably became furiously mad, from which condition he gradually settled down into harmless insanity. When, as I told you in my other letter I visited my old home in the fall of 1844, I found him still lingering in this wretched condition. In my poetizing mood I could not forget the impression his case made upon me.

Transcriptions of both cantos (under the title "My Childhood's Home I See Again") as they appeared in Lincoln's letters to Johnston can be read online through the Representative Poetry Online web site.

At the end of Lincoln's September 6 letter, he told Johnston that "if I should ever send another [poem], the subject will be a "Bear Hunt." In the next letter that Lincoln sent Johnston (February 25, 1847) Lincoln did in fact send Johnston another poem. Replying to Johnston's offer to publish the first two cantos of his poems, Lincoln wrote: "To say the least, I am not at all displeased with your proposal to publish the poetry, or doggerel, or whatever else it may be called, which I sent you. I consent that it may be done, together which the third canto, which I now send you." It is probable that the third canto Lincoln sent to Johnston was "The Bear Hunt."

Lincoln continued to compose poems in subsequent years, though none as substantial as those written in 1846. On September 28, 1858, Lincoln wrote the following verses "in the autograph album of Rosa Haggard, daughter of the proprietor of the hotel at Winchester, Illinois, where he stayed when speaking at that place on the same date":

To Rosa—

You are young, and I am older;

You are hopeful, I am not—

Enjoy life, ere it grow colder—

Pluck the roses ere they rot.

Teach your beau to heed the lay—

That sunshine soon is lost in shade—

That now's as good as any day—

To take thee, Rose, ere she fade.

Similarly, on September 30, 1858, Lincoln wrote the following verse to Rosa's sister Linnie Haggard:

To Linnie—

A sweet plaintive song did I hear,

And I fancied that she was the singer—

May emotions as pure, as that song set a-stir

Be the worst that the future shall bring her.

Lincoln's last documented verse was written July 19, 1863, in response to the North's victory in the Battle of Gettysburg:

Verse on Lee's Invasion of the North

Gen. Lees invasion of the North written by himself—

In eighteen sixty three, with pomp,

and mighty swell,

Me and Jeff's Confederacy, went

forth to sack Phil-del,

The Yankees they got arter us, and

giv us particular hell,

And we skedaddled back again,

And didn't sack Phil-del.

In 2004, news broke that a poem entitled "The Suicide's Soliloquy," published in the August 25, 1838, issue of the Sangamo Journal, may have been written by Lincoln. While many scholars believe that Lincoln is indeed the author of the poem, there is no consensus. The announcement of the poem's possible author first appeared in the 2004 Spring newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln Association. The text of the poem, along with the introduction that precedes it in the Sangamo Journal, follows below.

THE SUICIDE'S SOLILOQUY.

The following lines were said to have been found

near the bones of a man supposed to have committed

suicide, in a deep forest, on the Flat Branch of the

Sangamon, some time ago.

Here, where the lonely hooting owl

Sends forth his midnight moans,

Fierce wolves shall o'er my carcase growl,

Or buzzards pick my bones.

No fellow-man shall learn my fate,

Or where my ashes lie;

Unless by beasts drawn round their bait,

Or by the ravens' cry.

Yes! I've resolved the deed to do,

And this the place to do it:

This heart I'll rush a dagger through,

Though I in hell should rue it!

Hell! What is hell to one like me

Who pleasures never know;

By friends consigned to misery,

By hope deserted too?

To ease me of this power to think,

That through my bosom raves,

I'll headlong leap from hell's high brink,

And wallow in its waves.

Though devils yell, and burning chains

May waken long regret;

Their frightful screams, and piercing pains,

Will help me to forget.

Yes! I'm prepared, through endless night,

To take that fiery berth!

Think not with tales of hell to fright

Me, who am damn'd on earth!

Sweet steel! come forth from out your sheath,

And glist'ning, speak your powers;

Rip up the organs of my breath,

And draw my blood in showers!

I strike! It quivers in that heart

Which drives me to this end;

I draw and kiss the bloody dart,

My last—my only friend!

I

My childhood's home I see again,

And sadden with the view;

...

You are young, and I am older;

You are hopeful, I am not -

Enjoy life, ere it grow colder -

Pluck the roses ere they rot.

...

Here, where the lonely hooting owl

Sends forth his midnight moans,

Fierce wolves shall o’er my carcase growl,

Or buzzards pick my bones.

...

A wild-bear chace, didst never see?

Then hast thou lived in vain.

Thy richest bump of glorious glee,

Lies desert in thy brain.

...

Abraham Lincoln is my nam[e]

And with my pen I wrote the same

I wrote in both hast and speed

and left it here for fools to read

...