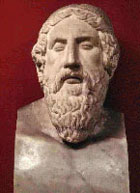

Homer

Homer Poems

Brave Menelaus son of Atreus now came to know that Patroclus had

fallen, and made his way through the front ranks clad in full armour

to bestride him. As a cow stands lowing over her first calf, even so

did yellow-haired Menelaus bestride Patroclus. He held his round

...

Now when Dawn in robe of saffron was hasting from the streams of

Oceanus, to bring light to mortals and immortals, Thetis reached the

ships with the armour that the god had given her. She found her son

fallen about the body of Patroclus and weeping bitterly. Many also

...

Now the other gods and the armed warriors on the plain slept

soundly, but Jove was wakeful, for he was thinking how to do honour to

Achilles, and destroyed much people at the ships of the Achaeans. In

the end he deemed it would be best to send a lying dream to King

...

Thus the Trojans in the city, scared like fawns, wiped the sweat

from off them and drank to quench their thirst, leaning against the

goodly battlements, while the Achaeans with their shields laid upon

their shoulders drew close up to the walls. But stern fate bade Hector

...

Now the other princes of the Achaeans slept soundly the whole

night through, but Agamemnon son of Atreus was troubled, so that he

could get no rest. As when fair Juno's lord flashes his lightning in

token of great rain or hail or snow when the snow-flakes whiten the

...

And now as Dawn rose from her couch beside Tithonus, harbinger of

light alike to mortals and immortals, Jove sent fierce Discord with

the ensign of war in her hands to the ships of the Achaeans. She

took her stand by the huge black hull of Ulysses' ship which was

...

So the son of Menoetius was attending to the hurt of Eurypylus

within the tent, but the Argives and Trojans still fought desperately,

nor were the trench and the high wall above it, to keep the Trojans in

check longer. They had built it to protect their ships, and had dug

...

Nestor was sitting over his wine, but the cry of battle did not

escape him, and he said to the son of Aesculapius, "What, noble

Machaon, is the meaning of all this? The shouts of men fighting by our

ships grow stronger and stronger; stay here, therefore, and sit over

...

Thus, then, did the Achaeans arm by their ships round you, O son

of Peleus, who were hungering for battle; while the Trojans over

against them armed upon the rise of the plain.

Meanwhile Jove from the top of many-delled Olympus, bade Themis

...

Thus did they make their moan throughout the city, while the

Achaeans when they reached the Hellespont went back every man to his

own ship. But Achilles would not let the Myrmidons go, and spoke to

his brave comrades saying, "Myrmidons, famed horsemen and my own

...

When the companies were thus arrayed, each under its own captain,

the Trojans advanced as a flight of wild fowl or cranes that scream

overhead when rain and winter drive them over the flowing waters of

Oceanus to bring death and destruction on the Pygmies, and they

...

With these words Hector passed through the gates, and his brother

Alexandrus with him, both eager for the fray. As when heaven sends a

breeze to sailors who have long looked for one in vain, and have

laboured at their oars till they are faint with toil, even so

...

Now the gods were sitting with Jove in council upon the golden floor

while Hebe went round pouring out nectar for them to drink, and as

they pledged one another in their cups of gold they looked down upon

the town of Troy. The son of Saturn then began to tease Juno,

...

But when their flight had taken them past the trench and the set

stakes, and many had fallen by the hands of the Danaans, the Trojans

made a halt on reaching their chariots, routed and pale with fear.

Jove now woke on the crests of Ida, where he was lying with

...

Thus did the Trojans watch. But Panic, comrade of blood-stained

Rout, had taken fast hold of the Achaeans and their princes were all

of them in despair. As when the two winds that blow from Thrace- the

north and the northwest- spring up of a sudden and rouse the fury of

...

Then Ulysses tore off his rags, and sprang on to the broad

pavement with his bow and his quiver full of arrows. He shed the

arrows on to the ground at his feet and said, "The mighty contest is

at an end. I will now see whether Apollo will vouchsafe it to me to

...

Now when Morning, clad in her robe of saffron, had begun to suffuse

light over the earth, Jove called the gods in council on the topmost

crest of serrated Olympus. Then he spoke and all the other gods gave

ear. "Hear me," said he, "gods and goddesses, that I may speak even as

...

Then Pallas Minerva put valour into the heart of Diomed, son of

Tydeus, that he might excel all the other Argives, and cover himself

with glory. She made a stream of fire flare from his shield and helmet

like the star that shines most brilliantly in summer after its bath in

...

Thence we went on to the Aeoli island where lives Aeolus son of

Hippotas, dear to the immortal gods. It is an island that floats (as

it were) upon the sea, iron bound with a wall that girds it. Now,

Aeolus has six daughters and six lusty sons, so he made the sons marry

...

And Ulysses answered, "King Alcinous, it is a good thing to hear a

bard with such a divine voice as this man has. There is nothing better

or more delightful than when a whole people make merry together,

with the guests sitting orderly to listen, while the table is loaded

...

Homer Biography

In the Western classical tradition, Homer is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature. When he lived is controversial. Herodotus estimates that Homer lived 400 years before Herodotus' own time, which would place him at around 850 BC; while other ancient sources claim that he lived much nearer to the supposed time of the Trojan War, in the early 12th century BC The formative influence played by the Homeric epics in shaping Greek culture was widely recognized, and Homer was described as the teacher of Greece.Homer's works, which are about fifty percent speeches, provided models in persuasive speaking and writing that were emulated throughout the ancient and medieval Greek worlds. Fragments of Homer account for nearly half of all identifiable Greek literary papyrus finds. Period For modern scholars "the date of Homer" refers not to an individual, but to the period when the epics were created. The consensus is that "the Iliad and the Odyssey date from around the 8th century BC, the Iliad being composed before the Odyssey, perhaps by some decades," i.e. earlier than Hesiod the Iliad being the oldest work of Western literature. Over the past few decades, some scholars have argued for a 7th century BC date. Some of those who argue that the Homeric poems developed gradually over a long period of time give an even later date for the composition of the poems; according to Gregory Nagy for example, they only became fixed texts in the 6th century BC. The question of the historicity of Homer the individual is known as the "Homeric question"; there is no reliable biographical information handed down from classical antiquity. The poems are generally seen as the culmination of many generations of oral story-telling, in a tradition with a well-developed formulaic system of poetic composition. Some scholars, such as Martin West, claim that "Homer" is "not the name of a historical poet, but a fictitious or constructed name." Life and legends "Homer" is a Greek name, attested in Aeolic-speaking areas, and although nothing definite is known about him, traditions arose purporting to give details of his birthplace and background. The satirist Lucian, in his True History, describes him as a Babylonian called Tigranes, who assumed the name Homer when taken "hostage" (homeros) by the Greeks. When the Emperor Hadrian asked the Oracle at Delphi about Homer, the Pythia proclaimed that he was Ithacan, the son of Epikaste and Telemachus, from the Odyssey. These stories were incorporated into the various Lives of Homer compiled from the Alexandrian period onwards. Homer is most frequently said to be born in the Ionian region of Asia Minor, at Smyrna, or on the island of Chios, dying on the Cycladic island of Ios. A connection with Smyrna seems to be alluded to in a legend that his original name was Melesigenes ("born of Meles", a river which flowed by that city), with his mother the nymph Kretheis. Internal evidence from the poems gives evidence of familiarity with the topography and place-names of this area of Asia Minor, for example, Homer refers to meadow birds at the mouth of the Caystros , a storm in the Icarian sea (Iliad 2.144ff.), and mentions that women in Maeonia and Caria stain ivory with scarlet . The association with Chios dates back to at least Semonides of Amorgos, who cited a famous line in the Iliad (6.146) as by "the man of Chios". An eponymous bardic guild, known as the Homeridae (sons of Homer), or Homeristae ('Homerizers') appears to have existed there, tracing descent from an ancestor of that name, or upholding their function as rhapsodes or "lay-stitchers" specialising in the recitation of Homeric poetry. Wilhelm Dörpfeld suggests that Homer had visited many of the places and regions which he describes in his epics, such as Mycenae, Troy, the palace of Odysseus at Ithaca and more. According to Diodorus Siculus, Homer had even visited Egypt. The poet's name is homophonous with ὅμηρος (hómēros), "hostage" (or "surety"), which is interpreted as meaning "he who accompanies; he who is forced to follow", or, in some dialects, "blind". This led to many tales that he was a hostage or a blind man. Traditions which assert that he was blind may have arisen from the meaning of the word in both Ionic, where the verbal form ὁμηρεύω (homēreúō) has the specialized meaning of "guide the blind", and the Aeolian dialect of Cyme, where ὅμηρος (hómēros) is synonymous with the standard Greek τυφλός (tuphlós), meaning 'blind'. The characterization of Homer as a blind bard goes back to some verses in the Delian Hymn to Apollo, the third of the Homeric Hymns, verses later cited to support this notion by Thucydides.The Cymean historian Ephorus held the same view, and the idea gained support in antiquity on the strength of a false etymology which derived his name from ho mḕ horṓn (ὁ μὴ ὁρῶν: "he who does not see"). Critics have long taken as self-referential a passage in the Odyssey describing a blind bard, Demodocus, in the court of the Phaeacian king, who recounts stories of Troy to the shipwrecked Odysseus. Many scholars take the name of the poet to be indicative of a generic function. Gregory Nagy takes it to mean "he who fits (the Song) together". ὁμηρέω (homēréō), another related verb, besides signifying "meet", can mean "(sing) in accord/tune". Some argue that "Homer" may have meant "he who puts the voice in tune" with dancing. Marcello Durante links "Homeros" to an epithet of Zeus as "god of the assemblies" and argues that behind the name lies the echo of an archaic word for "reunion", similar to the later Panegyris, denoting a formal assembly of competing minstrels. Some Ancient Lives depict Homer as a wandering minstrel, like Thamyris or Hesiod, who walked as far as Chalkis to sing at the funeral games of Amphidamas. We are given the image of a "blind, begging singer who hangs around with little people: shoemakers, fisherman, potters, sailors, elderly men in the gathering places of harbour towns". The poems, on the other hand, give us evidence of singers at the courts of the nobility. There is a strong aristocratic bias in the poems demonstrated by the lack of any major protagonists of non-aristocratic stock, and by episodes such as the beating down of the commoner Thersites by the king Odysseus for daring to criticize his superiors. In spite of this scholars are divided as to which category, if any, the court singer or the wandering minstrel, the historic "Homer" belonged. Works attributed to Homer The Greeks of the sixth and early fifth centuries BC understood by "Homer", generally, "the whole body of heroic tradition as embodied in hexameter verse". Thus, in addition to the Iliad and the Odyssey, there are "exceptional" epics which organize their respective themes on a "massive scale". Many other works were credited to Homer in antiquity, including the entire Epic Cycle. The genre included further poems on the Trojan War, such as the Little Iliad, the Nostoi, the Cypria, and the Epigoni, as well as the Theban poems about Oedipus and his sons. Other works, such as the corpus of Homeric Hymns, the comic mini-epic Batrachomyomachia ("The Frog-Mouse War"), and the Margites were also attributed to him, but this is now believed to be unlikely. Two other poems, the Capture of Oechalia and the Phocais were also assigned Homeric authorship, but the question of the identities of the authors of these various texts is even more problematic than that of the authorship of the two major epics. Problems of authorship The idea that Homer was responsible for just the two outstanding epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, did not win consensus until 350 BC. While many find it unlikely that both epics were composed by the same person, others argue that the stylistic similarities are too consistent to support the theory of multiple authorship. One view which attempts to bridge the differences holds that the Iliad was composed by "Homer" in his maturity, while the Odyssey was a work of his old age. The Batrachomyomachia, Homeric Hymns and cyclic epics are generally agreed to be later than the Iliad and the Odyssey. Most scholars agree that the Iliad and Odyssey underwent a process of standardisation and refinement out of older material beginning in the 8th century BC. An important role in this standardisation appears to have been played by the Athenian tyrant Hipparchus, who reformed the recitation of Homeric poetry at the Panathenaic festival. Many classicists hold that this reform must have involved the production of a canonical written text. Other scholars still support the idea that Homer was a real person. Since nothing is known about the life of this Homer, the common joke—also recycled with regard to Shakespeare—has it that the poems "were not written by Homer, but by another man of the same name." Samuel Butler argues, based on literary observations, that a young Sicilian woman wrote the Odyssey (but not the Iliad),an idea further pursued by Robert Graves in his novel Homer's Daughter and Andrew Dalby in Rediscovering Homer. Independent of the question of single authorship is the near-universal agreement, after the work of Milman Parry, that the Homeric poems are dependent on an oral tradition, a generations-old technique that was the collective inheritance of many singer-poets (aoidoi). An analysis of the structure and vocabulary of the Iliad and Odyssey shows that the poems contain many formulaic phrases typical of extempore epic traditions; even entire verses are at times repeated. Parry and his student Albert Lord pointed out that such elaborate oral tradition, foreign to today's literate cultures, is typical of epic poetry in a predominantly oral cultural milieu, the key words being "oral" and "traditional". Parry started with "traditional": the repetitive chunks of language, he said, were inherited by the singer-poet from his predecessors, and were useful to him in composition. Parry called these repetitive chunks "formulas". Exactly when these poems would have taken on a fixed written form is subject to debate. The traditional solution is the "transcription hypothesis", wherein a non-literate "Homer" dictates his poem to a literate scribe between the 8th and 6th centuries BC. The Greek alphabet was introduced in the early 8th century BC, so it is possible that Homer himself was of the first generation of authors who were also literate. The classicist Barry B. Powell suggests that the Greek alphabet was invented ca. 800 BC by one man, probably Homer, in order to write down oral epic poetry. More radical Homerists like Gregory Nagy contend that a canonical text of the Homeric poems as "scripture" did not exist until the Hellenistic period (3rd to 1st century BC). New methods try also to elucidate the question. Combining information technologies and statistics, the stylometry allows to scan various linguistic units: words, parts of speech, sounds... Based on the frequencies of Greek letters, a first study of Dietmar Najock particularly shows the internal cohesion of the Iliad and the Odysssey. Taking into account the repartition of the letters, a recent study of Stephan Vonfelt highlights the unity of the works of Homer compared to Hesiod. The thesis of modern Analysts being questioned, the debate remains open. Homeric studies The study of Homer is one of the oldest topics in scholarship, dating back to antiquity. The aims and achievements of Homeric studies have changed over the course of the millennia. In the last few centuries, they have revolved around the process by which the Homeric poems came into existence and were transmitted over time to us, first orally and later in writing. Some of the main trends in modern Homeric scholarship have been, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Analysis and Unitarianism (see Homeric Question), schools of thought which emphasized on the one hand the inconsistencies in, and on the other the artistic unity of, Homer; and in the 20th century and later Oral Theory, the study of the mechanisms and effects of oral transmission, and Neoanalysis, the study of the relationship between Homer and other early epic material. Homeric dialect The language used by Homer is an archaic version of Ionic Greek, with admixtures from certain other dialects, such as Aeolic Greek. It later served as the basis of Epic Greek, the language of epic poetry, typically in dactylic hexameter. Homeric style Aristotle remarks in his Poetics that Homer was unique among the poets of his time, focusing on a single unified theme or action in the epic cycle. The cardinal qualities of the style of Homer are well articulated by Matthew Arnold: [T]he translator of Homer should above all be penetrated by a sense of four qualities of his author:—that he is eminently rapid; that he is eminently plain and direct, both in the evolution of his thought and in the expression of it, that is, both in his syntax and in his words; that he is eminently plain and direct in the substance of his thought, that is, in his matter and ideas; and finally, that he is eminently noble. The peculiar rapidity of Homer is due in great measure to his use of hexameter verse. It is characteristic of early literature that the evolution of the thought, or the grammatical form of the sentence, is guided by the structure of the verse; and the correspondence which consequently obtains between the rhythm and the syntax—the thought being given out in lengths, as it were, and these again divided by tolerably uniform pauses—produces a swift flowing movement such as is rarely found when periods are constructed without direct reference to the metre. That Homer possesses this rapidity without falling into the corresponding faults, that is, without becoming either fluctuant or monotonous, is perhaps the best proof of his unequalled poetic skill. The plainness and directness of both thought and expression which characterise him were doubtless qualities of his age, but the author of the Iliad (similar to Voltaire, to whom Arnold happily compares him) must have possessed this gift in a surpassing degree. The Odyssey is in this respect perceptibly below the level of the Iliad. Rapidity or ease of movement, plainness of expression, and plainness of thought are not distinguishing qualities of the great epic poets Virgil, Dante, and Milton. On the contrary, they belong rather to the humbler epico-lyrical school for which Homer has been so often claimed. The proof that Homer does not belong to that school—and that his poetry is not in any true sense ballad poetry—is furnished by the higher artistic structure of his poems and, as regards style, by the fourth of the qualities distinguished by Arnold: the quality of nobleness. It is his noble and powerful style, sustained through every change of idea and subject, that finally separates Homer from all forms of ballad poetry and popular epic. Like the French epics, such as the Chanson de Roland, Homeric poetry is indigenous and, by the ease of movement and its resultant simplicity, distinguishable from the works of Dante, Milton and Virgil. It is also distinguished from the works of these artists by the comparative absence of underlying motives or sentiment. In Virgil's poetry, a sense of the greatness of Rome and Italy is the leading motive of a passionate rhetoric, partly veiled by the considered delicacy of his language. Dante and Milton are still more faithful exponents of the religion and politics of their time. Even the French epics display sentiments of fear and hatred of the Saracens; but, in Homer's works, the interest is purely dramatic. There is no strong antipathy of race or religion; the war turns on no political events; the capture of Troy lies outside the range of the Iliad; and even the protagonists are not comparable to the chief national heroes of Greece. So far as can be seen, the chief interest in Homer's works is that of human feeling and emotion, and of drama; indeed, his works are often referred to as "dramas". Greece according to the Iliad The excavations of Heinrich Schliemann at Hisarlik in the late 19th century provided initial evidence to scholars that there was an historical basis for the Trojan War. Research into oral epics in Serbo-Croatian and Turkic languages, pioneered by the aforementioned Parry and Lord, began convincing scholars that long poems could be preserved with consistency by oral cultures until they are written down. The decipherment of Linear B in the 1950s by Michael Ventris (and others) convinced many of a linguistic continuity between 13th century BC Mycenaean writings and the poems attributed to Homer. It is probable, therefore, that the story of the Trojan War as reflected in the Homeric poems derives from a tradition of epic poetry founded on a war which actually took place. It is crucial, however, not to underestimate the creative and transforming power of subsequent tradition: for instance, Achilles, the most important character of the Iliad, is strongly associated with southern Thessaly, but his legendary figure is interwoven into a tale of war whose kings were from the Peloponnese. Tribal wanderings were frequent, and far-flung, ranging over much of Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean. The epic weaves brilliantly the disiecta membra (scattered remains) of these distinct tribal narratives, exchanged among clan bards, into a monumental tale in which Greeks join collectively to do battle on the distant plains of Troy. Hero cult The Apotheosis of Homer, by Archelaus of Priene (marble relief, possibly 3rd century BC, now in the British Museum) In the Hellenistic period, Homer was the subject of a hero cult in several cities. A shrine, the Homereion, was devoted to him in Alexandria by Ptolemy IV Philopator in the late 3rd century BC. This shrine is described in Aelian's 3rd century AD work Varia Historia. He tells how Ptolemy "placed in a circle around the statue [of Homer] all the cities who laid claim to Homer" and mentions a painting of the poet by the artist Galaton, which apparently depicted Homer in the aspect of Oceanus as the source of all poetry. A marble relief, found in Italy but thought to have been sculpted in Egypt, depicts the apotheosis of Homer. It shows Ptolemy and his wife or sister Arsinoe III standing beside a seated poet, flanked by figures from the Odyssey and Iliad, with the nine Muses standing above them and a procession of worshippers approaching an altar, believed to represent the Alexandrine Homereion. Apollo, the god of music and poetry, also appears, along with a female figure tentatively identified as Mnemosyne, the mother of the Muses. Zeus, the king of the gods, presides over the proceedings. The relief demonstrates vividly that the Greeks considered Homer not merely a great poet but the divinely inspired reservoir of all literature. Homereia also stood at Chios, Ephesus, and Smyrna, which were among the city-states that claimed to be his birthplace. Strabo (14.1.37) records an Homeric temple in Smyrna with an ancient xoanon or cult statue of the poet. He also mentions sacrifices carried out to Homer by the inhabitants of Argos, presumably at another Homereion. Transmission and publication Though evincing many features characteristic of oral poetry, the Iliad and Odyssey were at some point committed to writing. The Greek script, adapted from a Phoenician syllabary around 800 BC, made possible the notation of the complex rhythms and vowel clusters that make up hexameter verse. Homer's poems appear to have been recorded shortly after the alphabet's invention: an inscription from Ischia in the Bay of Naples, ca. 740 BC, appears to refer to a text of the Iliad; likewise, illustrations seemingly inspired by the Polyphemus episode in the Odyssey are found on Samos, Mykonos and in Italy, dating from the first quarter of the seventh century BC. We have little information about the early condition of the Homeric poems, but in the second century BC, Alexandrian editors stabilized this text from which all modern texts descend. In late antiquity, knowledge of Greek declined in Latin-speaking western Europe and, along with it, knowledge of Homer's poems. It was not until the fifteenth century AD that Homer's work began to be read once more in Italy. By contrast it was continually read and taught in the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire where the majority of the classics also survived. The first printed edition appeared in 1488 (edited by Demetrios Chalkokondyles and published by Bernardus Nerlius, Nerius Nerlius, and Demetrius Damilas in Florence, Italy).)

The Best Poem Of Homer

The Iliad: Book 17

Brave Menelaus son of Atreus now came to know that Patroclus had

fallen, and made his way through the front ranks clad in full armour

to bestride him. As a cow stands lowing over her first calf, even so

did yellow-haired Menelaus bestride Patroclus. He held his round

shield and his spear in front of him, resolute to kill any who

should dare face him. But the son of Panthous had also noted the body,

and came up to Menelaus saying, "Menelaus, son of Atreus, draw back,

leave the body, and let the bloodstained spoils be. I was first of the

Trojans and their brave allies to drive my spear into Patroclus, let

me, therefore, have my full glory among the Trojans, or I will take

aim and kill you."

To this Menelaus answered in great anger "By father Jove, boasting

is an ill thing. The pard is not more bold, nor the lion nor savage

wild-boar, which is fiercest and most dauntless of all creatures, than

are the proud sons of Panthous. Yet Hyperenor did not see out the days

of his youth when he made light of me and withstood me, deeming me the

meanest soldier among the Danaans. His own feet never bore him back to

gladden his wife and parents. Even so shall I make an end of you

too, if you withstand me; get you back into the crowd and do not

face me, or it shall be worse for you. Even a fool may be wise after

the event."

Euphorbus would not listen, and said, "Now indeed, Menelaus, shall

you pay for the death of my brother over whom you vaunted, and whose

wife you widowed in her bridal chamber, while you brought grief

unspeakable on his parents. I shall comfort these poor people if I

bring your head and armour and place them in the hands of Panthous and

noble Phrontis. The time is come when this matter shall be fought

out and settled, for me or against me."

As he spoke he struck Menelaus full on the shield, but the spear did

not go through, for the shield turned its point. Menelaus then took

aim, praying to father Jove as he did so; Euphorbus was drawing

back, and Menelaus struck him about the roots of his throat, leaning

his whole weight on the spear, so as to drive it home. The point

went clean through his neck, and his armour rang rattling round him as

he fell heavily to the ground. His hair which was like that of the

Graces, and his locks so deftly bound in bands of silver and gold,

were all bedrabbled with blood. As one who has grown a fine young

olive tree in a clear space where there is abundance of water- the

plant is full of promise, and though the winds beat upon it from every

quarter it puts forth its white blossoms till the blasts of some

fierce hurricane sweep down upon it and level it with the ground- even

so did Menelaus strip the fair youth Euphorbus of his armour after

he had slain him. Or as some fierce lion upon the mountains in the

pride of his strength fastens on the finest heifer in a herd as it

is feeding- first he breaks her neck with his strong jaws, and then

gorges on her blood and entrails; dogs and shepherds raise a hue and

cry against him, but they stand aloof and will not come close to

him, for they are pale with fear- even so no one had the courage to

face valiant Menelaus. The son of Atreus would have then carried off

the armour of the son of Panthous with ease, had not Phoebus Apollo

been angry, and in the guise of Mentes chief of the Cicons incited

Hector to attack him. "Hector," said he, "you are now going after

the horses of the noble son of Aeacus, but you will not take them;

they cannot be kept in hand and driven by mortal man, save only by

Achilles, who is son to an immortal mother. Meanwhile Menelaus son

of Atreus has bestridden the body of Patroclus and killed the

noblest of the Trojans, Euphorbus son of Panthous, so that he can

fight no more."

The god then went back into the toil and turmoil, but the soul of

Hector was darkened with a cloud of grief; he looked along the ranks

and saw Euphorbus lying on the ground with the blood still flowing

from his wound, and Menelaus stripping him of his armour. On this he

made his way to the front like a flame of fire, clad in his gleaming

armour, and crying with a loud voice. When the son of Atreus heard

him, he said to himself in his dismay, "Alas! what shall I do? I may

not let the Trojans take the armour of Patroclus who has fallen

fighting on my behalf, lest some Danaan who sees me should cry shame

upon me. Still if for my honour's sake I fight Hector and the

Trojans single-handed, they will prove too many for me, for Hector

is bringing them up in force. Why, however, should I thus hesitate?

When a man fights in despite of heaven with one whom a god

befriends, he will soon rue it. Let no Danaan think ill of me if I

give place to Hector, for the hand of heaven is with him. Yet, if I

could find Ajax, the two of us would fight Hector and heaven too, if

we might only save the body of Patroclus for Achilles son of Peleus.

This, of many evils would be the least."

While he was thus in two minds, the Trojans came up to him with

Hector at their head; he therefore drew back and left the body,

turning about like some bearded lion who is being chased by dogs and

men from a stockyard with spears and hue and cry, whereon he is

daunted and slinks sulkily off- even so did Menelaus son of Atreus

turn and leave the body of Patroclus. When among the body of his

men, he looked around for mighty Ajax son of Telamon, and presently

saw him on the extreme left of the fight, cheering on his men and

exhorting them to keep on fighting, for Phoebus Apollo had spread a

great panic among them. He ran up to him and said, "Ajax, my good

friend, come with me at once to dead Patroclus, if so be that we may

take the body to Achilles- as for his armour, Hector already has it."

These words stirred the heart of Ajax, and he made his way among the

front ranks, Menelaus going with him. Hector had stripped Patroclus of

his armour, and was dragging him away to cut off his head and take the

body to fling before the dogs of Troy. But Ajax came up with his

shield like wall before him, on which Hector withdrew under shelter of

his men, and sprang on to his chariot, giving the armour over to the

Trojans to take to the city, as a great trophy for himself; Ajax,

therefore, covered the body of Patroclus with his broad shield and

bestrode him; as a lion stands over his whelps if hunters have come

upon him in a forest when he is with his little ones- in the pride and

fierceness of his strength he draws his knit brows down till they

cover his eyes- even so did Ajax bestride the body of Patroclus, and

by his side stood Menelaus son of Atreus, nursing great sorrow in

his heart.

Then Glaucus son of Hippolochus looked fiercely at Hector and

rebuked him sternly. "Hector," said he, "you make a brave show, but in

fight you are sadly wanting. A runaway like yourself has no claim to

so great a reputation. Think how you may now save your town and

citadel by the hands of your own people born in Ilius; for you will

get no Lycians to fight for you, seeing what thanks they have had

for their incessant hardships. Are you likely, sir, to do anything

to help a man of less note, after leaving Sarpedon, who was at once

your guest and comrade in arms, to be the spoil and prey of the

Danaans? So long as he lived he did good service both to your city and

yourself; yet you had no stomach to save his body from the dogs. If

the Lycians will listen to me, they will go home and leave Troy to its

fate. If the Trojans had any of that daring fearless spirit which lays

hold of men who are fighting for their country and harassing those who

would attack it, we should soon bear off Patroclus into Ilius. Could

we get this dead man away and bring him into the city of Priam, the

Argives would readily give up the armour of Sarpedon, and we should

get his body to boot. For he whose squire has been now killed is the

foremost man at the ships of the Achaeans- he and his close-fighting

followers. Nevertheless you dared not make a stand against Ajax, nor

face him, eye to eye, with battle all round you, for he is a braver

man than you are."

Hector scowled at him and answered, "Glaucus, you should know

better. I have held you so far as a man of more understanding than any

in all Lycia, but now I despise you for saying that I am afraid of

Ajax. I fear neither battle nor the din of chariots, but Jove's will

is stronger than ours; Jove at one time makes even a strong man draw

back and snatches victory from his grasp, while at another he will set

him on to fight. Come hither then, my friend, stand by me and see

indeed whether I shall play the coward the whole day through as you

say, or whether I shall not stay some even of the boldest Danaans from

fighting round the body of Patroclus."

As he spoke he called loudly on the Trojans saying, "Trojans,

Lycians, and Dardanians, fighters in close combat, be men, my friends,

and fight might and main, while I put on the goodly armour of

Achilles, which I took when I killed Patroclus."

With this Hector left the fight, and ran full speed after his men

who were taking the armour of Achilles to Troy, but had not yet got

far. Standing for a while apart from the woeful fight, he changed

his armour. His own he sent to the strong city of Ilius and to the

Trojans, while he put on the immortal armour of the son of Peleus,

which the gods had given to Peleus, who in his age gave it to his son;

but the son did not grow old in his father's armour.

When Jove, lord of the storm-cloud, saw Hector standing aloof and

arming himself in the armour of the son of Peleus, he wagged his

head and muttered to himself saying, "A! poor wretch, you arm in the

armour of a hero, before whom many another trembles, and you reck

nothing of the doom that is already close upon you. You have killed

his comrade so brave and strong, but it was not well that you should

strip the armour from his head and shoulders. I do indeed endow you

with great might now, but as against this you shall not return from

battle to lay the armour of the son of Peleus before Andromache."

The son of Saturn bowed his portentous brows, and Hector fitted

the armour to his body, while terrible Mars entered into him, and

filled his whole body with might and valour. With a shout he strode in

among the allies, and his armour flashed about him so that he seemed

to all of them like the great son of Peleus himself. He went about

among them and cheered them on- Mesthles, Glaucus, Medon,

Thersilochus, Asteropaeus, Deisenor and Hippothous, Phorcys,

Chromius and Ennomus the augur. All these did he exhort saying,

"Hear me, allies from other cities who are here in your thousands,

it was not in order to have a crowd about me that I called you

hither each from his several city, but that with heart and soul you

might defend the wives and little ones of the Trojans from the

fierce Achaeans. For this do I oppress my people with your food and

the presents that make you rich. Therefore turn, and charge at the

foe, to stand or fall as is the game of war; whoever shall bring

Patroclus, dead though he be, into the hands of the Trojans, and shall

make Ajax give way before him, I will give him one half of the

spoils while I keep the other. He will thus share like honour with

myself."

When he had thus spoken they charged full weight upon the Danaans

with their spears held out before them, and the hopes of each ran high

that he should force Ajax son of Telamon to yield up the body- fools

that they were, for he was about to take the lives of many. Then

Ajax said to Menelaus, "My good friend Menelaus, you and I shall

hardly come out of this fight alive. I am less concerned for the

body of Patroclus, who will shortly become meat for the dogs and

vultures of Troy, than for the safety of my own head and yours. Hector

has wrapped us round in a storm of battle from every quarter, and

our destruction seems now certain. Call then upon the princes of the

Danaans if there is any who can hear us."

Menelaus did as he said, and shouted to the Danaans for help at

the top of his voice. "My friends," he cried, "princes and counsellors

of the Argives, all you who with Agamemnon and Menelaus drink at the

public cost, and give orders each to his own people as Jove vouchsafes

him power and glory, the fight is so thick about me that I cannot

distinguish you severally; come on, therefore, every man unbidden, and

think it shame that Patroclus should become meat and morsel for Trojan

hounds."

Fleet Ajax son of Oileus heard him and was first to force his way

through the fight and run to help him. Next came Idomeneus and

Meriones his esquire, peer of murderous Mars. As for the others that

came into the fight after these, who of his own self could name them?

The Trojans with Hector at their head charged in a body. As a

great wave that comes thundering in at the mouth of some heaven-born

river, and the rocks that jut into the sea ring with the roar of the

breakers that beat and buffet them- even with such a roar did the

Trojans come on; but the Achaeans in singleness of heart stood firm

about the son of Menoetius, and fenced him with their bronze

shields. Jove, moreover, hid the brightness of their helmets in a

thick cloud, for he had borne no grudge against the son of Menoetius

while he was still alive and squire to the descendant of Aeacus;

therefore he was loth to let him fall a prey to the dogs of his foes

the Trojans, and urged his comrades on to defend him.

At first the Trojans drove the Achaeans back, and they withdrew from

the dead man daunted. The Trojans did not succeed in killing any

one, nevertheless they drew the body away. But the Achaeans did not

lose it long, for Ajax, foremost of all the Danaans after the son of

Peleus alike in stature and prowess, quickly rallied them and made

towards the front like a wild boar upon the mountains when he stands

at bay in the forest glades and routs the hounds and lusty youths that

have attacked him- even so did Ajax son of Telamon passing easily in

among the phalanxes of the Trojans, disperse those who had

bestridden Patroclus and were most bent on winning glory by dragging

him off to their city. At this moment Hippothous brave son of the

Pelasgian Lethus, in his zeal for Hector and the Trojans, was dragging

the body off by the foot through the press of the fight, having

bound a strap round the sinews near the ancle; but a mischief soon

befell him from which none of those could save him who would have

gladly done so, for the son of Telamon sprang forward and smote him on

his bronze-cheeked helmet. The plumed headpiece broke about the

point of the weapon, struck at once by the spear and by the strong

hand of Ajax, so that the bloody brain came oozing out through the

crest-socket. His strength then failed him and he let Patroclus'

foot drop from his hand, as he fell full length dead upon the body;

thus he died far from the fertile land of Larissa, and never repaid

his parents the cost of bringing him up, for his life was cut short

early by the spear of mighty Ajax. Hector then took aim at Ajax with a

spear, but he saw it coming and just managed to avoid it; the spear

passed on and struck Schedius son of noble Iphitus, captain of the

Phoceans, who dwelt in famed Panopeus and reigned over much people; it

struck him under the middle of the collar-bone the bronze point went

right through him, coming out at the bottom of his shoulder-blade, and

his armour rang rattling round him as he fell heavily to the ground.

Ajax in his turn struck noble Phorcys son of Phaenops in the middle of

the belly as he was bestriding Hippothous, and broke the plate of

his cuirass; whereon the spear tore out his entrails and he clutched

the ground in his palm as he fell to earth. Hector and those who

were in the front rank then gave ground, while the Argives raised a

loud cry of triumph, and drew off the bodies of Phorcys and Hippothous

which they stripped presently of their armour.

The Trojans would now have been worsted by the brave Achaeans and

driven back to Ilius through their own cowardice, while the Argives,

so great was their courage and endurance, would have achieved a

triumph even against the will of Jove, if Apollo had not roused

Aeneas, in the likeness of Periphas son of Epytus, an attendant who

had grown old in the service of Aeneas' aged father, and was at all

times devoted to him. In his likeness, then, Apollo said, "Aeneas, can

you not manage, even though heaven be against us, to save high

Ilius? I have known men, whose numbers, courage, and self-reliance

have saved their people in spite of Jove, whereas in this case he

would much rather give victory to us than to the Danaans, if you would

only fight instead of being so terribly afraid."

Aeneas knew Apollo when he looked straight at him, and shouted to

Hector saying, "Hector and all other Trojans and allies, shame on us

if we are beaten by the Achaeans and driven back to Ilius through

our own cowardice. A god has just come up to me and told me that

Jove the supreme disposer will be with us. Therefore let us make for

the Danaans, that it may go hard with them ere they bear away dead

Patroclus to the ships."

As he spoke he sprang out far in front of the others, who then

rallied and again faced the Achaeans. Aeneas speared Leiocritus son of

Arisbas, a valiant follower of Lycomedes, and Lycomedes was moved with

pity as he saw him fall; he therefore went close up, and speared

Apisaon son of Hippasus shepherd of his people in the liver under

the midriff, so that he died; he had come from fertile Paeonia and was

the best man of them all after Asteropaeus. Asteropaeus flew forward

to avenge him and attack the Danaans, but this might no longer be,

inasmuch as those about Patroclus were well covered by their

shields, and held their spears in front of them, for Ajax had given

them strict orders that no man was either to give ground, or to

stand out before the others, but all were to hold well together

about the body and fight hand to hand. Thus did huge Ajax bid them,

and the earth ran red with blood as the corpses fell thick on one

another alike on the side of the Trojans and allies, and on that of

the Danaans; for these last, too, fought no bloodless fight though

many fewer of them perished, through the care they took to defend

and stand by one another.

Thus did they fight as it were a flaming fire; it seemed as though

it had gone hard even with the sun and moon, for they were hidden over

all that part where the bravest heroes were fighting about the dead

son of Menoetius, whereas the other Danaans and Achaeans fought at

their ease in full daylight with brilliant sunshine all round them,

and there was not a cloud to be seen neither on plain nor mountain.

These last moreover would rest for a while and leave off fighting, for

they were some distance apart and beyond the range of one another's

weapons, whereas those who were in the thick of the fray suffered both

from battle and darkness. All the best of them were being worn out

by the great weight of their armour, but the two valiant heroes,

Thrasymedes and Antilochus, had not yet heard of the death of

Patroclus, and believed him to be still alive and leading the van

against the Trojans; they were keeping themselves in reserve against

the death or rout of their own comrades, for so Nestor had ordered

when he sent them from the ships into battle.

Thus through the livelong day did they wage fierce war, and the

sweat of their toil rained ever on their legs under them, and on their

hands and eyes, as they fought over the squire of the fleet son of

Peleus. It was as when a man gives a great ox-hide all drenched in fat

to his men, and bids them stretch it; whereon they stand round it in a

ring and tug till the moisture leaves it, and the fat soaks in for the

many that pull at it, and it is well stretched- even so did the two

sides tug the dead body hither and thither within the compass of but a

little space- the Trojans steadfastly set on drag ing it into Ilius,

while the Achaeans were no less so on taking it to their ships; and

fierce was the fight between them. Not Mars himself the lord of hosts,

nor yet Minerva, even in their fullest fury could make light of such a

battle.

Such fearful turmoil of men and horses did Jove on that day ordain

round the body of Patroclus. Meanwhile Achilles did not know that he

had fallen, for the fight was under the wall of Troy a long way off

the ships. He had no idea, therefore, that Patroclus was dead, and

deemed that he would return alive as soon as he had gone close up to

the gates. He knew that he was not to sack the city neither with nor

without himself, for his mother had often told him this when he had

sat alone with her, and she had informed him of the counsels of

great Jove. Now, however, she had not told him how great a disaster

had befallen him in the death of the one who was far dearest to him of

all his comrades.

The others still kept on charging one another round the body with

their pointed spears and killing each other. Then would one say, "My

friends, we can never again show our faces at the ships- better, and

greatly better, that earth should open and swallow us here in this

place, than that we should let the Trojans have the triumph of bearing

off Patroclus to their city."

The Trojans also on their part spoke to one another saying,

"Friends, though we fall to a man beside this body, let none shrink

from fighting." With such words did they exhort each other. They

fought and fought, and an iron clank rose through the void air to

the brazen vault of heaven. The horses of the descendant of Aeacus

stood out of the fight and wept when they heard that their driver

had been laid low by the hand of murderous Hector. Automedon,

valiant son of Diores, lashed them again and again; many a time did he

speak kindly to them, and many a time did he upbraid them, but they

would neither go back to the ships by the waters of the broad

Hellespont, nor yet into battle among the Achaeans; they stood with

their chariot stock still, as a pillar set over the tomb of some

dead man or woman, and bowed their heads to the ground. Hot tears fell

from their eyes as they mourned the loss of their charioteer, and

their noble manes drooped all wet from under the yokestraps on

either side the yoke.

The son of Saturn saw them and took pity upon their sorrow. He

wagged his head, and muttered to himself, saying, "Poor things, why

did we give you to King Peleus who is a mortal, while you are

yourselves ageless and immortal? Was it that you might share the

sorrows that befall mankind? for of all creatures that live and move

upon the earth there is none so pitiable as he is- still, Hector son

of Priam shall drive neither you nor your chariot. I will not have it.

It is enough that he should have the armour over which he vaunts so

vainly. Furthermore I will give you strength of heart and limb to bear

Automedon safely to the ships from battle, for I shall let the Trojans

triumph still further, and go on killing till they reach the ships;

whereon night shall fall and darkness overshadow the land."

As he spoke he breathed heart and strength into the horses so that

they shook the dust from out of their manes, and bore their chariot

swiftly into the fight that raged between Trojans and Achaeans. Behind

them fought Automedon full of sorrow for his comrade, as a vulture

amid a flock of geese. In and out, and here and there, full speed he

dashed amid the throng of the Trojans, but for all the fury of his

pursuit he killed no man, for he could not wield his spear and keep

his horses in hand when alone in the chariot; at last, however, a

comrade, Alcimedon, son of Laerces son of Haemon caught sight of him

and came up behind his chariot. "Automedon," said he, "what god has

put this folly into your heart and robbed you of your right mind, that

you fight the Trojans in the front rank single-handed? He who was your

comrade is slain, and Hector plumes himself on being armed in the

armour of the descendant of Aeacus."

Automedon son of Diores answered, "Alcimedon, there is no one else

who can control and guide the immortal steeds so well as you can, save

only Patroclus- while he was alive- peer of gods in counsel. Take then

the whip and reins, while I go down from the car and fight.

Alcimedon sprang on to the chariot, and caught up the whip and

reins, while Automedon leaped from off the car. When Hector saw him he

said to Aeneas who was near him, "Aeneas, counsellor of the

mail-clad Trojans, I see the steeds of the fleet son of Aeacus come

into battle with weak hands to drive them. I am sure, if you think

well, that we might take them; they will not dare face us if we both

attack them."

The valiant son of Anchises was of the same mind, and the pair

went right on, with their shoulders covered under shields of tough dry

ox-hide, overlaid with much bronze. Chromius and Aretus went also with

them, and their hearts beat high with hope that they might kill the

men and capture the horses- fools that they were, for they were not to

return scatheless from their meeting with Automedon, who prayed to

father Jove and was forthwith filled with courage and strength

abounding. He turned to his trusty comrade Alcimedon and said,

"Alcimedon, keep your horses so close up that I may feel their

breath upon my back; I doubt that we shall not stay Hector son of

Priam till he has killed us and mounted behind the horses; he will

then either spread panic among the ranks of the Achaeans, or himself

be killed among the foremost."

On this he cried out to the two Ajaxes and Menelaus, "Ajaxes

captains of the Argives, and Menelaus, give the dead body over to them

that are best able to defend it, and come to the rescue of us

living; for Hector and Aeneas who are the two best men among the

Trojans, are pressing us hard in the full tide of war. Nevertheless

the issue lies on the lap of heaven, I will therefore hurl my spear

and leave the rest to Jove."

He poised and hurled as he spoke, whereon the spear struck the round

shield of Aretus, and went right through it for the shield stayed it

not, so that it was driven through his belt into the lower part of his

belly. As when some sturdy youth, axe in hand, deals his blow behind

the horns of an ox and severs the tendons at the back of its neck so

that it springs forward and then drops, even so did Aretus give one

bound and then fall on his back the spear quivering in his body till

it made an end of him. Hector then aimed a spear at Automedon but he

saw it coming and stooped forward to avoid it, so that it flew past

him and the point stuck in the ground, while the butt-end went on

quivering till Mars robbed it of its force. They would then have

fought hand to hand with swords had not the two Ajaxes forced their

way through the crowd when they heard their comrade calling, and

parted them for all their fury- for Hector, Aeneas, and Chromius

were afraid and drew back, leaving Aretus to lie there struck to the

heart. Automedon, peer of fleet Mars, then stripped him of his

armour and vaunted over him saying, "I have done little to assuage

my sorrow for the son of Menoetius, for the man I have killed is not

so good as he was."

As he spoke he took the blood-stained spoils and laid them upon

his chariot; then he mounted the car with his hands and feet all

steeped in gore as a lion that has been gorging upon a bull.

And now the fierce groanful fight again raged about Patroclus, for

Minerva came down from heaven and roused its fury by the command of

far-seeing Jove, who had changed his mind and sent her to encourage

the Danaans. As when Jove bends his bright bow in heaven in token to

mankind either of war or of the chill storms that stay men from

their labour and plague the flocks- even so, wrapped in such radiant

raiment, did Minerva go in among the host and speak man by man to

each. First she took the form and voice of Phoenix and spoke to

Menelaus son of Atreus, who was standing near her. "Menelaus," said

she, "it will be shame and dishonour to you, if dogs tear the noble

comrade of Achilles under the walls of Troy. Therefore be staunch, and

urge your men to be so also."

Menelaus answered, "Phoenix, my good old friend, may Minerva

vouchsafe me strength and keep the darts from off me, for so shall I

stand by Patroclus and defend him; his death has gone to my heart, but

Hector is as a raging fire and deals his blows without ceasing, for

Jove is now granting him a time of triumph."

Minerva was pleased at his having named herself before any of the

other gods. Therefore she put strength into his knees and shoulders,

and made him as bold as a fly, which, though driven off will yet

come again and bite if it can, so dearly does it love man's blood-

even so bold as this did she make him as he stood over Patroclus and

threw his spear. Now there was among the Trojans a man named Podes,

son of Eetion, who was both rich and valiant. Hector held him in the

highest honour for he was his comrade and boon companion; the spear of

Menelaus struck this man in the girdle just as he had turned in

flight, and went right through him. Whereon he fell heavily forward,

and Menelaus son of Atreus drew off his body from the Trojans into the

ranks of his own people.

Apollo then went up to Hector and spurred him on to fight, in the

likeness of Phaenops son of Asius who lived in Abydos and was the most

favoured of all Hector's guests. In his likeness Apollo said, "Hector,

who of the Achaeans will fear you henceforward now that you have

quailed before Menelaus who has ever been rated poorly as a soldier?

Yet he has now got a corpse away from the Trojans single-handed, and

has slain your own true comrade, a man brave among the foremost, Podes

son of Eetion.

A dark cloud of grief fell upon Hector as he heard, and he made

his way to the front clad in full armour. Thereon the son of Saturn

seized his bright tasselled aegis, and veiled Ida in cloud: he sent

forth his lightnings and his thunders, and as he shook his aegis he

gave victory to the Trojans and routed the Achaeans.

The panic was begun by Peneleos the Boeotian, for while keeping

his face turned ever towards the foe he had been hit with a spear on

the upper part of the shoulder; a spear thrown by Polydamas had grazed

the top of the bone, for Polydamas had come up to him and struck him

from close at hand. Then Hector in close combat struck Leitus son of

noble Alectryon in the hand by the wrist, and disabled him from

fighting further. He looked about him in dismay, knowing that never

again should he wield spear in battle with the Trojans. While Hector

was in pursuit of Leitus, Idomeneus struck him on the breastplate over

his chest near the nipple; but the spear broke in the shaft, and the

Trojans cheered aloud. Hector then aimed at Idomeneus son of Deucalion

as he was standing on his chariot, and very narrowly missed him, but

the spear hit Coiranus, a follower and charioteer of Meriones who

had come with him from Lyctus. Idomeneus had left the ships on foot

and would have afforded a great triumph to the Trojans if Coiranus had

not driven quickly up to him, he therefore brought life and rescue

to Idomeneus, but himself fell by the hand of murderous Hector. For

Hector hit him on the jaw under the ear; the end of the spear drove

out his teeth and cut his tongue in two pieces, so that he fell from

his chariot and let the reins fall to the ground. Meriones gathered

them up from the ground and took them into his own hands, then he said

to Idomeneus, "Lay on, till you get back to the ships, for you must

see that the day is no longer ours."

On this Idomeneus lashed the horses to the ships, for fear had taken

hold upon him.

Ajax and Menelaus noted how Jove had turned the scale in favour of

the Trojans, and Ajax was first to speak. "Alas," said he, "even a

fool may see that father Jove is helping the Trojans. All their

weapons strike home; no matter whether it be a brave man or a coward

that hurls them, Jove speeds all alike, whereas ours fall each one

of them without effect. What, then, will be best both as regards

rescuing the body, and our return to the joy of our friends who will

be grieving as they look hitherwards; for they will make sure that

nothing can now check the terrible hands of Hector, and that he will

fling himself upon our ships. I wish that some one would go and tell

the son of Peleus at once, for I do not think he can have yet heard

the sad news that the dearest of his friends has fallen. But I can see

not a man among the Achaeans to send, for they and their chariots

are alike hidden in darkness. O father Jove, lift this cloud from over

the sons of the Achaeans; make heaven serene, and let us see; if you

will that we perish, let us fall at any rate by daylight."

Father Jove heard him and had compassion upon his tears. Forthwith

he chased away the cloud of darkness, so that the sun shone out and

all the fighting was revealed. Ajax then said to Menelaus, "Look,

Menelaus, and if Antilochus son of Nestor be still living, send him at

once to tell Achilles that by far the dearest to him of all his

comrades has fallen."

Menelaus heeded his words and went his way as a lion from a

stockyard- the lion is tired of attacking the men and hounds, who keep

watch the whole night through and will not let him feast on the fat of

their herd. In his lust of meat he makes straight at them but in vain,

for darts from strong hands assail him, and burning brands which daunt

him for all his hunger, so in the morning he slinks sulkily away- even

so did Menelaus sorely against his will leave Patroclus, in great fear

lest the Achaeans should be driven back in rout and let him fall

into the hands of the foe. He charged Meriones and the two Ajaxes

straitly saying, "Ajaxes and Meriones, leaders of the Argives, now

indeed remember how good Patroclus was; he was ever courteous while

alive, bear it in mind now that he is dead."

With this Menelaus left them, looking round him as keenly as an

eagle, whose sight they say is keener than that of any other bird-

however high he may be in the heavens, not a hare that runs can escape

him by crouching under bush or thicket, for he will swoop down upon it

and make an end of it- even so, O Menelaus, did your keen eyes range

round the mighty host of your followers to see if you could find the

son of Nestor still alive. Presently Menelaus saw him on the extreme

left of the battle cheering on his men and exhorting them to fight

boldly. Menelaus went up to him and said, "Antilochus, come here and

listen to sad news, which I would indeed were untrue. You must see

with your own eyes that heaven is heaping calamity upon the Danaans,

and giving victory to the Trojans. Patroclus has fallen, who was the

bravest of the Achaeans, and sorely will the Danaans miss him. Run

instantly to the ships and tell Achilles, that he may come to rescue

the body and bear it to the ships. As for the armour, Hector already

has it."

Antilochus was struck with horror. For a long time he was

speechless; his eyes filled with tears and he could find no utterance,

but he did as Menelaus had said, and set off running as soon as he had

given his armour to a comrade, Laodocus, who was wheeling his horses

round, close beside him.

Thus, then, did he run weeping from the field, to carry the bad news

to Achilles son of Peleus. Nor were you, O Menelaus, minded to succour

his harassed comrades, when Antilochus had left the Pylians- and

greatly did they miss him- but he sent them noble Thrasymedes, and

himself went back to Patroclus. He came running up to the two Ajaxes

and said, "I have sent Antilochus to the ships to tell Achilles, but

rage against Hector as he may, he cannot come, for he cannot fight

without armour. What then will be our best plan both as regards

rescuing the dead, and our own escape from death amid the battle-cries

of the Trojans?"

Ajax answered, "Menelaus, you have said well: do you, then, and

Meriones stoop down, raise the body, and bear it out of the fray,

while we two behind you keep off Hector and the Trojans, one in

heart as in name, and long used to fighting side by side with one

another."

On this Menelaus and Meriones took the dead man in their arms and

lifted him high aloft with a great effort. The Trojan host raised a

hue and cry behind them when they saw the Achaeans bearing the body

away, and flew after them like hounds attacking a wounded boar at

the loo of a band of young huntsmen. For a while the hounds fly at him

as though they would tear him in pieces, but now and again he turns on

them in a fury, scaring and scattering them in all directions- even so

did the Trojans for a while charge in a body, striking with sword

and with spears pointed ai both the ends, but when the two Ajaxes

faced them and stood at bay, they would turn pale and no man dared

press on to fight further about the dead.

In this wise did the two heroes strain every nerve to bear the

body to the ships out of the fight. The battle raged round them like

fierce flames that when once kindled spread like wildfire over a city,

and the houses fall in the glare of its burning- even such was the

roar and tramp of men and horses that pursued them as they bore

Patroclus from the field. Or as mules that put forth all their

strength to draw some beam or great piece of ship's timber down a

rough mountain-track, and they pant and sweat as they, go even so

did Menelaus and pant and sweat as they bore the body of Patroclus.

Behind them the two Ajaxes held stoutly out. As some wooded

mountain-spur that stretches across a plain will turn water and

check the flow even of a great river, nor is there any stream strong

enough to break through it- even so did the two Ajaxes face the

Trojans and stern the tide of their fighting though they kept

pouring on towards them and foremost among them all was Aeneas son

of Anchises with valiant Hector. As a flock of daws or starlings

fall to screaming and chattering when they see a falcon, foe to i'll

small birds, come soaring near them, even so did the Achaean youth

raise a babel of cries as they fled before Aeneas and Hector,

unmindful of their former prowess. In the rout of the Danaans much

goodly armour fell round about the trench, and of fighting there was

no end.

Translated by Samuel Butler

Homer Comments

Please amend your otherwisw excellent website by giving Homer's approximate date to c 1100 BC. The initials BCE are unnecessarily offensive

O the great epic-poet, I have also a desire to write an epic-poem in Bangla, my mother language, on our great leader Bangabandhu.

Aristotle remarks in his Poetics that Homer was unique among the poets of his time, and indeed, the presumed author of the Iliad and the Odyssey must assuredly be one of the greatest of the world’s literary artists. He is also one of the most influential authors in the widest sense, for the two epics provided the basis of Greek education and culture throughout the Classical age and formed the backbone of humane education down to the time of the Roman Empire and the spread of Christianity...

The incomparable at his throne; Homer the legend. He is as alive as his works of literature; to me his envy, i want to die and live like he did.

oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof oof

Homer Quotes

The generation of mankind is like the generation of leaves. The wind scatters the leaves on the ground, but the living tree burgeons with leaves again in the spring.

Hunger is insolent, and will be fed.

I was inspired by the great poetic insperation of Homer..........His great epics impacted to change the entire western culture..............i love homer.......!