Mutsuo Takahashi

Mutsuo Takahashi Poems

Once, on some occasion, I said to Mr. Shigeo Washisu,2 'If the Ah's

and Oh's disappeared from your writings, they'd feel so much more

modern.' Well, here's what he said in reply: 'Ah, you're right. Oh,

that's true, you're right.' Two years since he descended into the

Underworld and, stripped of his temporary personality known as

Shigeo Washisu, joined the common herd of the dead, I wanted to

call to him using Ah's and Oh's abundantly. Ah, Oh, true enough, I

wanted to call to him.

...

that dove gives it up, he asked

he puts out, I answered

OO what's he into, he inquired further

...

The island, draped in golden clouds,

does not exist anywhere on the chart.

...

There is no one who has seen the book.

Yet there is no one who doubts its existence.

It sleeps in the depths of the distant clouds dark before dawn.

...

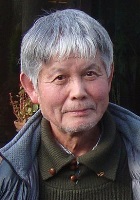

Mutsuo Takahashi Biography

Mutsuo Takahashi (高橋 睦郎 Takahashi Mutsuo, born December 15, 1937) is one of the most prominent and prolific male poets, essayists, and writers of contemporary Japan, with more than three dozen collections of poetry, several works of prose, dozens books of essays, and several major literary prizes to his name. He is especially well known for his open writing about male homoeroticism. He currently lives in the seaside town of Zushi, several kilometers south of Yokohama, Japan. Born in 1937 in the rural southern island of Kyushu, Takahashi spent his early years living in the countryside of Japan. As Takahashi describes in his memoirs Twelve Views from the Distance (十二の遠景 Jū-ni no enkei) published in 1970, his father, a factory worker in a metal plant, died of pneumonia when Takahashi was one hundred and five days old, leaving his mother to fend for herself in the world. Taking advantage of the opportunities presented by the expanding Japanese empire, she left Takahashi and his sisters with their grandparents in the rural town of Nōgata and went to Tientsin in mainland China to be with a lover. Due to his grandparents’ poverty, Takahashi spent much time with extended family and other neighbors. Especially important to him during this time was an uncle that served a pivotal figure in Takahashi’s development, serving as a masculine role model and object of love. Again, however, historical fate intervened, and the uncle, whom Takahashi later described in many early poems, was sent to the battlefield in Burma, where illness claimed his life. After Takahashi’s mother returned from the mainland, they went to live in the port of Moji, just as the bombings of the mainland by the Allied powers intensified. Takahashi’s memoirs describe that although he hated the war, World War II provided a chaotic and frightening circus for his classmates, who would go to gawk at the wreckage of the B-29s that fell from the sky and to watch ships blow up at sea, destroyed by naval mines. Takahashi writes that when the war came to an end, he felt a great sense of relief. In his memoirs and interviews, Takahashi has mentioned that in the time he spent with his schoolmates, he became increasingly aware of his own sexual attraction towards men. This became a common subject in the first book of poetry he published in 1959. After a bout of tuberculosis, Takahashi graduated from the Fukuoka University of Education, and in 1962 moved to Tokyo. For many years, he worked at an advertising company, but in the meantime, he wrote a good deal of poetry. His first book to receive national attention was Rose Tree, Fake Lovers (薔薇の木・にせの恋人たち Bara no ki, nise no koibito-tachi), an anthology published in 1964 that describes male-male erotic love in bold and direct language. A laudatory review from the critic Jun Etō appeared in the daily newspaper Asahi shimbun with Takahashi’s photograph—an unusual instance of a poet’s photograph included in the paper’s survey of literature. About the same time, Takahashi sent the collection to the novelist Yukio Mishima who contacted him and offered to use his name to help promote Takahashi’s work. The two shared a close relationship and friendship that lasted until Mishima’s suicide in 1970. Other close friends Takahashi made about this time include Tatsuhiko Shibusawa who translated the Marquis de Sade into Japanese, the surreal poet Chimako Tada who shared Takahashi's interest in classical Greece, the poet Shigeo Washisu who was also interested in the classics and the existential ramifications of homoeroticism. With the latter two writers, Takahashi cooperated to create the literary journal The Symposium (饗宴 Kyōen) named after Plato’s famous dialogue.This interest in eroticism and existentialism, in turn, is a reflection of a larger existential trend in the literature and culture of Japan during the 1960s and 1970s. Homoeroticism remained an important theme in his poetry written in free verse through the 1970s, including the long poem Ode (頌 Homeuta), which the publisher Winston Leyland has called “the great gay poem of the 20th century.” Many of these early works have been translated into English by Hiroaki Sato and reprinted in the collection Partings at Dawn: An Anthology of Japanese Gay Literature. About the same time, Takahashi started writing prose. In 1970, he published Twelve Views from the Distance about his early life and the novella The Sacred Promontory (聖なる岬 Sei naru misaki) about his own erotic awakening. In 1972, he wrote A Legend of a Holy Place (聖所伝説 Seisho densetsu), a surrealistic novella inspired by his own experiences during a forty-day trip to New York City in which Donald Richie led him through the gay, underground spots of the city. In 1974, he released Zen’s Pilgrimage of Virtue (善の遍歴 Zen no henreki), a homoerotic and often extremely humorous reworking of a legend of Sudhana found in the Buddhist classic Avatamsaka Sutra. Around 1975, Takahashi's writing began to explore a wider range of themes, such as the destiny of mankind, Takahashi’s travels to many nations around the world, and relationships in the modern world. It was with this broadening of themes that Takahashi’s poetry began to earn an increasingly broad audience. As with his early writing, Takahashi’s later writing shows a high degree of erudition, including a thorough awareness of the history of world literature and art. In fact, many of his collections published from the 1980s onward, include poems either dedicated to or about important authors around the world, including Jorge Luis Borges, Jean Genet, Ezra Pound, and Chimako Tada,—each a homage to an important literary predecessor. For instance, in 2010, Takahashi has also produced a slim book of poems to accompany a 2010 exhibition of the work of the American artist Joseph Cornell. Although Takahashi has been most visibly active in the realm of free verse poetry, he has also written traditional Japanese verse (both tanka and haiku poetry), novels, Nō and Kyōgen plays, reworkings of ancient Greek dramas and epic poetry, many works of literary criticism, and a libretto for an opera by the contemporary Japanese composer Akira Miyoshi. Since the broadening of Takahashi’s themes in the 1970s and his retirement from the advertising agency in the 1980s, the pace of his publication has only increased. He has been the recipient of a number of important literary prizes in Japan, such as the Rekitei Prize, the Yomiuri Literary Prize, the Takami Jun Prize, the Modern Poetry Hanatsubaki Prize, and the Shika Bungakukan Prize, and in 2000, he earned the prestigious Kunshō award for his contributions to modern Japanese literature. Takahashi presently lives in the seaside city of Zushi, ten kilometers from Yokohama. His poems have been translated into languages as diverse as Chinese, Norwegian, Spanish, and Afrikaans. He frequently gives readings and talks around the world.)

The Best Poem Of Mutsuo Takahashi

Ah, Oh

Once, on some occasion, I said to Mr. Shigeo Washisu,2 'If the Ah's

and Oh's disappeared from your writings, they'd feel so much more

modern.' Well, here's what he said in reply: 'Ah, you're right. Oh,

that's true, you're right.' Two years since he descended into the

Underworld and, stripped of his temporary personality known as

Shigeo Washisu, joined the common herd of the dead, I wanted to

call to him using Ah's and Oh's abundantly. Ah, Oh, true enough, I

wanted to call to him.

Ah, this land is sick.

Oh, is the soil there fertile?

Ah, what thrives here are stones and weeds.

Oh, do a lot of heads with disjointed neck bones fructify?

Ah, both poetry and potatoes are skinny and dry.

Oh, are the words exploding like the nuts of the dead?

(Ah, Oh, the nuts of the dead, shattered brainpans, also called

scrotums.)

Ah, the underground river escapes the vertically shaking earth's crust.

Oh, does the thick river haze of oblivion cover the ground?

Ah, I dig and dig, but only yellowed white hair.

Oh, is the pubic hair of the soil glistening wet?

Ah, I seek and seek, but only despair turned brownish white.

Oh, is even despair refreshing again and again?

(Ah, Oh, there, even despair revives again and again.)

Ah, the handle of a hoe can only become dry and break into two.

Oh, is the steel amply soaked in the night air?

Ah, the nails can only become deformed and crack into numberless

fissures.

Oh, do the nails and whiskers continue to grow night and day?

Ah, the eyes and the breasts become wrinkled and irritatingly pointed.

Oh, are the breezes through the trees black and delicate?

(Ah, Oh, the trees of the Underworld are equipped with eyes and

breasts.)

Ah, the starved babies weep, impatient with the nipples that only give

blood.

Oh, are even the old, smelly mouths satiated with milk?

Ah, under the man's excitement, the woman is the fire that burns

midsummer thorns.

Oh, is lust properly kept cooled?

Ah, here the fire, too, is frazzled.

Oh, are the flames velvety and pliant?

(Ah, Oh, our fire is a clumsy copy of the fire of the Underworld.)

Ah, it merely scorches uselessly and doesn't purify anything.

Oh, do burnt things learn of the peace of the ashes?

Ah, the dog that has swallowed the sun rolls about on the horizon.

Oh, does the eternal twilight change the barking dog into a gentle

shadow? .

Ah, I look up at the uphill path and, with my brow knit, continue

to ask.

Oh, he continues to descend on the other side of the path, wiping

off his sweat.

(Ah, Oh, his ears will never hear my voice.

That can never happen. Ah, Oh.)