Charles Kenneth Williams

Charles Kenneth Williams Poems

A young mother on a motor scooter stopped at a traffic light, her little son perched

on the ledge between her legs; she in a gleaming helmet, he in a replica of it, smaller, but

the same color and just as shiny. His visor is swung shut, hers is open.

...

If that someone who's me yet not me yet who judges me is always with me,

as he is, shouldn't he have been there when I said so long ago that thing

I said?

...

Kids once carried tin soldiers in their pockets as charms

against being afraid, but how trust soldiers these days

not to load up, aim, blast the pants off your legs?

...

Spring: the first morning when that one true block of sweet, laminar,

complex scent arrives

from somewhere west and I keep coming to lean on the sill, glorying in

...

Chop, hack, slash; chop, hack, slash; cleaver, boning knife, ax—

not even the clumsiest clod of a butcher could do this so crudely,

time, as do you, dismember me, render me, leave me slop in a pail,

...

1

Thank goodness we were able to wipe the Neanderthals out, beastly things,

from our mountains, our tundra—that way we had all the meat we might need.

Thus the butcher can display under our very eyes his hands on the block,

and never refer to the rooms hidden behind where dissections are effected,

where flesh is reduced to its shivering atoms and remade for our delectation

as cubes, cylinders, barely material puddles of admixtured horror and blood.

Rembrandt knew of all this—isn't his flayed beef carcass really a caveman?

It's Christ also, of course, but much more a troglodyte such as we no longer are.

Vanished those species—begone!—those tribes, those peoples, those nations—

Myrmidon, Ottoman, Olmec, Huron, and Kush: gone, gone, and goodbye.

2

But back to the chamber of torture, to Rembrandt, who was telling us surely

that hoisted with such cables and hung from such hooks we too would reveal

within us intricate layerings of color and pain: alive the brush is with pain,

aglow with the cruelties of crimson, the cooled, oblivious ivory of our innards.

Fling out the hooves of your hands! Open your breast, pluck out like an Aztec

your heart howling its Cro-Magnon cries that compel to battles of riddance!

Our own planet at last, where purged of wilderness, homesickness, prowling,

we're no longer compelled to devour our enemies' brains, thanks to our butcher,

who inhabits this palace, this senate, this sentried, barbed-wire enclosure

where dare enter none but subservient breeze; bent, broken blossom; dry rain.

...

Another drought morning after a too brief dawn downpour,

unaccountable silvery glitterings on the leaves of the withering maples—

I think of a troop of the blissful blessed approaching Dante,

"a hundred spheres shining," he rhapsodizes, "the purest pearls…"

then of the frightening brilliants myriad gleam in my lamp

of the eyes of the vast swarm of bats I found once in a cave,

a chamber whose walls seethed with a spaceless carpet of creatures,

their cacophonous, keen, insistent, incessant squeakings and squealings

churning the warm, rank, cloying air; of how one,

perfectly still among all the fitfully twitching others,

was looking straight at me, gazing solemnly, thoughtfully up

from beneath the intricate furl of its leathery wings

as though it couldn't believe I was there, or were trying to place me,

to situate me in the gnarl we'd evolved from, and now,

the trees still heartrendingly asparkle, Dante again,

this time the way he'll refer to a figure he meets as "the life of…"

not the soul, or person, the life, and once more the bat, and I,

our lives in that moment together, our lives, our lives,

his with no vision of celestial splendor, no poem,

mine with no flight, no unblundering dash through the dark,

his without realizing it would, so soon, no longer exist,

mine having to know for us both that everything ends,

world, after-world, even their memory, steamed away

like the film of uncertain vapor of the last of the luscious rain.

...

Some dictator or other had gone into exile, and now reports were coming about his regime,

the usual crimes, torture, false imprisonment, cruelty and corruption, but then a detail:

that the way his henchmen had disposed of enemies was by hammering nails into their skulls.

Horror, then, what mind does after horror, after that first feeling that you'll never catch your breath,

mind imagines—how not be annihilated by it?—the preliminary tap, feels it in the tendons of the hand,

feels the way you do with your nail when you're fixing something, making something, shelves, a bed;

the first light tap to set the slant, and then the slightly harder tap, to em-bed the tip a little more ...

No, no more: this should be happening in myth, in stone, or paint, not in reality, not here;

it should be an emblem of itself, not itself, something that would mean, not really have to happen,

something to go out, expand in implication from that unmoved mass of matter in the breast;

as in the image of an anguished face, in grief for us, not us as us, us as in a myth, a moral tale,

a way to tell the truth that grief is limitless, a way to tell us we must always understand

it's we who do such things, we who set the slant, embed the tip, lift the sledge and drive the nail,

drive the nail which is the axis upon which turns the brutal human world upon the world.

...

On the metro, I have to ask a young woman to move the packages beside her to make room for me;

she's reading, her foot propped on the seat in front of her, and barely looks up as she pulls them to her.

I sit, take out my own book—Cioran, The Temptation to Exist—and notice her glancing up from hers

to take in the title of mine, and then, as Gombrowicz puts it, she "affirms herself physically," that is,

becomes present in a way she hadn't been before: though she hasn't moved, she's allowed herself

to come more sharply into focus, be more accessible to my sensual perception, so I can't help but remark

her strong figure and very tan skin—(how literally golden young women can look at the end of summer.)

She leans back now, and as the train rocks and her arm brushes mine she doesn't pull it away;

she seems to be allowing our surfaces to unite: the fine hairs on both our forearms, sensitive, alive,

achingly alive, bring news of someone touched, someone sensed, and thus acknowledged, known.

I understand that in no way is she offering more than this, and in truth I have no desire for more,

but it's still enough for me to be taken by a surge, first of warmth then of something like its opposite:

a memory—a girl I'd mooned for from afar, across the table from me in the library in school now,

our feet I thought touching, touching even again, and then, with all I craved that touch to mean,

my having to realize it wasn't her flesh my flesh for that gleaming time had pressed, but a table leg.

The young woman today removes her arm now, stands, swaying against the lurch of the slowing train,

and crossing before me brushes my knee and does that thing again, asserts her bodily being again,

(Gombrowicz again), then quickly moves to the door of the car and descends, not once looking back,

(to my relief not looking back), and I allow myself the thought that though I must be to her again

as senseless as that table of my youth, as wooden, as unfeeling, perhaps there was a moment I was not.

...

A girl who, in 1971, when I was living by myself, painfully lonely, bereft, depressed,

offhandedly mentioned to me in a conversation with some friends that although at first she'd found me—

I can't remember the term, some dated colloquialism signifying odd, unacceptable, out-of-things—

she'd decided that I was after all all right ... twelve years later she comes back to me from nowhere

and I realize that it wasn't my then irrepressible, unselective, incessant sexual want she meant,

which, when we'd been introduced, I'd naturally aimed at her and which she'd easily deflected,

but that she'd thought I really was, in myself, the way I looked and spoke and acted,

what she was saying, creepy, weird, whatever, and I am taken with a terrible humiliation.

...

I was walking home down a hill near our house

on a balmy afternoon

under the blossoms

Of the pear trees that go flamboyantly mad here

every spring with

their burgeoning forth

When a young man turned in from a corner singing

no it was more of

a cadenced shouting

Most of which I couldn't catch I thought because

the young man was

black speaking black

It didn't matter I could tell he was making his

song up which pleased

me he was nice-looking

Husky dressed in some style of big pants obviously

full of himself

hence his lyrical flowing over

We went along in the same direction then he noticed

me there almost

beside him and 'Big'

He shouted-sang 'Big' and I thought how droll

to have my height

incorporated in his song

So I smiled but the face of the young man showed nothing

he looked

in fact pointedly away

And his song changed 'I'm not a nice person'

he chanted 'I'm not

I'm not a nice person'

No menace was meant I gathered no particular threat

but he did want

to be certain I knew

That if my smile implied I conceived of anything like concord

between us I should forget it

That's all nothing else happened his song became

indecipherable to

me again he arrived

Where he was going a house where a girl in braids

waited for him on

the porch that was all

No one saw no one heard all the unasked and

unanswered questions

were left where they were

It occurred to me to sing back 'I'm not a nice

person either' but I

couldn't come up with a tune

Besides I wouldn't have meant it nor he have believed

it both of us

knew just where we were

In the duet we composed the equation we made

the conventions to

which we were condemned

Sometimes it feels even when no one is there that

someone something

is watching and listening

Someone to rectify redo remake this time again though

no one saw nor

heard no one was there

...

An ax-shattered

bedroom window

the wall above

still smutted with

soot the wall

beneath still

soiled with

soak and down

on the black

of the pavement

a mattress its ticking

half eaten away

the end where

the head would

have been with

a nauseous bite

burnt away

and beside it

an all at once

meaningless heap

of soiled sodden

clothing one

shoe a jacket

once white

the vain matters

a life gathers

about it symbols

of having once

cried out to itself

who art thou?

then again who

wouldst thou be?

...

Difficult to know whether humans are inordinately anxious

about crisis, calamity, disaster, or unknowingly crave them.

These horrific conditionals, these expected unexpecteds,

we dwell on them, flinch, feint, steel ourselves:

but mightn't our forebodings actually precede anxiety?

Isn't so much sheer heedfulness emblematic of desire?

How do we come to believe that wrenching ourselves to attention

is the most effective way for dealing with intimations of catastrophe?

Consciousness atremble: might what makes it so

not be the fear of what the future might or might not bring,

but the wish for fear, for concentration, vigilance?

As though life were more convincing resonating like a blade.

Of course, we're rarely swept into events, other than domestic tumult,

from which awful consequences will ensue. Fortunately rarely.

And yet we sweat as fervently

for the most insipid issues of honor and unrealized ambition.

Lost brothership. Lost lust. We engorge our little sorrows,

beat our drums, perform our dances of aversion.

Always, "These gigantic inconceivables."

Always, "What will have been done to me?"

And so we don our mental armor,

flex, thrill, pay the strict attention we always knew we should.

A violent alertness, the muscularity of risk,

though still the secret inward cry: What else, what more?

...

Furiously a crane

in the scrapyard out of whose grasp

a car it meant to pick up slipped,

lifts and lets fall, lifts and lets fall

the steel ton of its clenched pincers

onto the shuddering carcass

which spurts fragments of anguished glass

until it's sufficiently crushed

to be hauled up and flung onto

the heap from which one imagines

it'll move on to the shredding

or melting down that awaits it.

Also somewhere a crow

with less evident emotion

punches its beak through the dead

breast of a dove or albino

sparrow until it arrives at

a coil of gut it can extract,

then undo with a dexterous twist

an oily stretch just the right length

to be devoured, the only

suggestion of violation

the carrion jerked to one side

in involuntary dismay.

Splayed on the soiled pavement

the dove or sparrow; dismembered

in the tangled remnants of itself

the wreck, the crane slamming once more

for good measure into the all

but dematerialized hulk,

then luxuriously swaying

away, as, gorged, glutted, the crow

with savage care unfurls the full,

luminous glitter of its wings,

so we can preen, too, for so much

so well accomplished, so well seen.

...

That astonishing thing that happens when you crack a needle-awl into a block of ice:

the way a perfect section through it crazes into gleaming fault-lines, fractures, facets;

dazzling silvery deltas that in one too-quick-to-capture instant madly complicate the cosmos of its innards.

Radiant now with spines and spikes, aggressive barbs of glittering light, a treasure horde of light,

when you stab it with the awl again it comes apart in nearly equal segments, both faces sadly grainy, gnawed at, dull.

What was called an ice-house was a dark, low place, of raw, unpainted wood,

always black with melted ice or ice as yet ungelled;

there was saw-dust, and saw-dust's tantalizing, half-sweet odor, which, so cold, seemed to pierce directly to the brain.

You'd step onto a low-roofed porch, someone would materialize,

take up great tongs and with precise, placating movements like a lion-tamer's slide an ice block from its row.

Take the awl again yourself now, thrust, and when the block splits do it yet again, again;

watch it disassemble into smaller fragments, crystal after fissured crystal.

Or if not the puncturing blade, try to make a metaphor, like Kafka's frozen sea within:

take into your arms the cake of actual ice, make a figure of its ponderous inertness,

of the way its quickly wetting chill against your breast would frighten you and make you let it drop.

Imagine then how even if it shattered and began to liquefy,

the hope would still remain that if you acted quickly, gathering up the slithery, perversely skittish ovals,

they might be refrozen and the mass reconstituted, with precious little of its brilliance lost,

just this lucent shimmer on the rough, raised grain of water-rotten floor,

just this drop as sweet and warm as blood evaporating on your tongue.

...

chances are we will sink quietly back

into oblivion without a ripple

we will go back into the face

down through the mortars as though it hadn't happened

earth: I'll remember you

you were the mother you made pain

I'll grind my thorax against you for the last time

and put my hand on you again to comfort you

sky: could we forget?

we were the same as you were

we couldn't wait to get back sleeping

we'd have done anything to be sleeping

and trees angels for being thrust up here

and stones for cracking in my bare hands

because you foreknew

there was no vengeance for being here

when we were flesh we were eaten

when we were metal we were burned back

there was no death anywhere but now

when we were men when we became it

...

I was lugging my death from Kampala to Krakow.

Death, what a ridiculous load you can be,

like the world trembling on Atlas's shoulders.

In Kampala I'd wondered why the people, so poor,

didn't just kill me. Why don't they kill me?

In Krakow I must have fancied I'd find poets to talk to.

I still believed then I'd domesticated my death,

that he'd no longer gnaw off my fingers and ears.

We even had parties together: "Happy," said death,

and gave me my present, a coffin, my coffin,

made in Kampala, with a sliding door in its lid,

to look through, at the sky, at the birds, at Kampala.

That was his way, I soon understood, of reverting

to talon and snarl, for the door refused to come open:

no sky, no bird, no poets, no Krakow.

Catherine came to me then, came to me then,

"Open your eyes, mon amour," but death

had undone me, my knuckles were raw as an ape's,

my mind slid like a sad-ankled skate, and no matter

what Catherine was saying, was sighing, was singing,

"Mon amour, mon amour," the door stayed shut, oh, shut.

I heard trees being felled, skinned, smoothed,

hammered together as coffins. I heard death

snorting and stamping, impatient to be hauled off, away.

But here again was Catherine, sighing, and singing,

and the tiny carved wooden door slid ajar, just enough:

the sky, one single bird, Catherine: just enough.

...

One branch, I read, of a species of chimpanzees has something like territorial wars,

and when the . . . army, I suppose you'd call it, of one tribe prevails and captures an enemy,"Several males hold a hand or foot of the rival so the victim can be damaged at will."

This is so disquieting: if beings with whom we share so many genes can be this cruel,

what hope for us? Still, "rival," "victim," "will"—don't such anthropomorphic terms

make those simians' social-political conflicts sound more brutal than they are?

The chimps Catherine and I saw on their island sanctuary in Uganda we loathed.

Unlike the pacific gorillas in the forest of Bwindi, they fought, dementedly shrieked,

the dominant male lorded it over the rest; they were, in all, too much like us.

Another island from my recent reading, where Columbus, on his last voyage,

encountering some "Indians" who'd greeted him with curiosity and warmth, wrote,

before he chained and enslaved them, "They don't even know how to kill each other."

It's occurred to me I've read enough—at my age all it does is confirm my sadness.

Surely the papers: war, terror, torture, corruption—they're like broken glass in the mind.

Back when I knew I knew nothing, I read all the time, poems, novels, philosophy, myth,

but I hardly glanced at the news, there was a distance between what could happen

and the part of myself I felt with: now everything's so tight against me I hardly can move.

The Analects say people in the golden age weren't aware they were governed; they just lived.

Could I have passed through my own golden age and not even known I was there?

Some gold: nuclear rockets aimed at your head, racism, sexism, contempt for the poor.

And there I was, reading. What did I learn? Everything, nothing, too little, too much . . .

Just enough to get me here: a long-faced, white-haired ape with a book, still turning the page.

...

When Blackstone the magician cut a woman in half in the Branford theater

near the famous Lincoln statue in already part way down the chute Newark,

he used a gigantic buzz saw, and the woman let out a shriek that out-shrieked

the whirling blade and drilled directly into the void of our little boy crotches.

That must be when we learned that real men were supposed to hurt women,

make them cry then leave them, because we saw the blade go in, right in,

her waist was bare—look!—and so, in her silvery garlanded bra, shining,

were her breasts, oh round, silvery garlanded tops of breasts shining.

Which must be when we went insane, and were sent to drive our culture insane . . .

"Show me your breasts, please." "Shame on you, hide your breasts: shame."

Nothing else mattered, just silvery garlanded breasts, and still she shrieked,

the blade was still going in, under her breasts, and nothing else mattered.

Oh Branford theater, with your scabby plaster and threadbare scrim,

you didn't matter, and Newark, your tax-base oozing away to the suburbs,

you didn't matter, nor your government by corruption, nor swelling slums—

you were invisible now, those breasts had made you before our eyes vanish,

as Blackstone would make doves then a horse before our eyes vanish,

as at the end factories and business from our vanquished city would vanish.

Oh Blackstone, gesturing, conjuring, with your looming, piercing glare.

Oh gleaming, hurtling blade, oh drawn-out scream, oh perfect, thrilling arc of pain.

...

Face powder, gun powder, talcum of anthrax,

shavings of steel, crematoria ash, chips

of crumbling poetry paper—all these in my lock-box,

and dust, tanks, tempests, temples of dust.

Saw-, silk-, chalk-dust and chaff,

the dust the drool of a bull swinging its head

as it dreams its death

slobs out on; dust even from that scoured,

scraped littoral of the Aegean,

troops streaming screaming across it

at those who that day, that age or forever

would be foe, worthy of being dust for.

Last, hovering dust of the harvest, brief

as the half-instant hitch in the flight

of the hawk, as the poplets of light

through the leaves of the bronzing maples.

Animal dust, mineral, mental, all hoarded

not in the jar of sexy Pandora, not

in the ark where the dust of the holy aspiring

to congeal as glorious mud-thing still writhes—

Just this leathery, crackled, obsolete box,

heart-sized or brain, rusted lock shattered,

hinge howling with glee to be lifted again . . .

Face powder, gun powder, dust, darling dust.

...

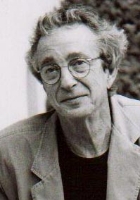

Charles Kenneth Williams Biography

C. K. Williams (born Charles Kenneth Williams on November 4, 1936) is an American poet, critic and translator. Williams has won nearly every major poetry award. Flesh and Blood won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1987. Repair (1999) won the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, was a National Book Award finalist and won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. The Singing won the National Book Award, 2003 and in 2005 Williams received the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. The 2012 film Tar related aspects of Williams' life using his poetry. C. K. Williams grew up in Newark, New Jersey and graduated from Columbia High School in Maplewood. He later briefly attended Bucknell University and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. While at Penn he studied with the romantic scholar, Morse Peckham, and spent a great deal of time in the circle of young architects who studied with and worked for the great architect Louis Kahn. In an essay, “Beginnings,” he acknowledges Kahn’s dedication and patience as essential to his notion of the life of an artist. Williams lived for a period in Philadelphia, where he worked for a number of years as a part-time psychotherapist for adolescents and young adults, a ghost-writer and editor, then began teaching, first at the YM-YWHA in Philadelphia, then at several universities in Pennsylvania, Beaver College, Drexel, and Franklin and Marshall. He subsequently taught at many other universities, including Columbia, NYU, Boston University, the University of California, both at Irvine and Berkeley, before finally becoming a professor at George Mason University, then moving in 1995 to Princeton University, where he has taught poetry workshops and translation ever since. He met his present wife, Catherine Mauger, a French jeweler, in 1973, and they have a son who is now a noted painter, Jed Williams. He has a daughter from an earlier marriage, Jessie Williams Burns, who is a writer. He lives half the year near Princeton, and the rest in Normandy in France. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.)

The Best Poem Of Charles Kenneth Williams

They Call This

A young mother on a motor scooter stopped at a traffic light, her little son perched

on the ledge between her legs; she in a gleaming helmet, he in a replica of it, smaller, but

the same color and just as shiny. His visor is swung shut, hers is open.

As I pull up beside them on my bike, the mother is leaning over to embrace the child,

whispering something in his ear, and I'm shaken, truly shaken, by the wish, the need, to

have those slim strong arms contain me in their sanctuary of affection.

Though they call this regression, though that implies a going back to some other

state and this has never left me, this fundamental pang of being too soon torn from a bliss

that promises more bliss, no matter that the scooter's fenders are dented, nor that as it

idles it pops, clears its throat, growls.